“Keeping the Torch Burning” - editing an Olympics book for the Guardian

The Olympic countdown clock in Trafalgar Square on the day I finally finished writing and editing my Guardian ebook about the Games.

With barely three-and-a-half days to go to London’s amazing Olympic opening ceremony, I finally finished editing a book about terror, protest and dissent at the Olympic Games for the Guardian. It is based on a series of blog posts I wrote in the run-up to Beijing in 2008, supplemented with a generous delve into the Guardian’s archive of over a hundred years of reporting the Olympics.

As has become the custom, here is the “DVD extra behind-the-scenes editor’s commentary” on putting the book together.

“Keeping the Torch Burning: Terror, Protest and the Games” - £2.99 on Kindle

Start with the hardest part...

The low point of the history of the Olympics is the terrorist attack on Israeli athletes in Munich in 1972. In reframing my original series of blog posts for the Guardian, I decided to start by writing the chapter about 1972. It seemed to me that getting the tone of that right informed the tone of the whole of the book.

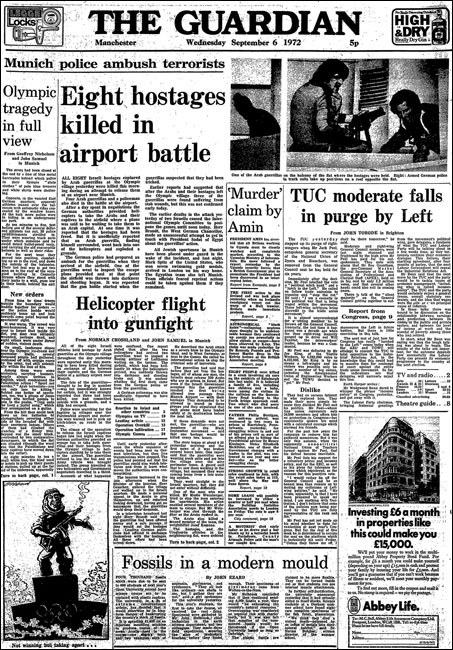

The Guardian front page announces the Munich terrorist attack on the Olympic Games

Adding contemporary reporting brings challenges. I included a piece entitled “Killers from nowhere land” which John Ezard wrote for the Guardian a couple of days after the shoot-out. It opens with John quoting a London cabbie who says “I can’t quite decide if their cause is good or bad, but I think anyone who allows it to lead to this kind of thing is only fit for public hanging.”

Ezard was on his was to interview PLO spokesman Said Hammami. Including the view of the PLO risks it looking like an “apologist” piece for the atrocity. Hammami is quoted as saying:

“Look at the Olympic Games - one of the greatest assemblies of the world’s youth community. The people who did this were probably youths. They have been ignored since 1948 and so they have ignored everything. Why? Because they are not recognised. People laugh at me when I mention Palestine to them. You ask me why? Because, they say, what is Palestine? It does not exist. We have got to prove to the world that it does exist.”

I thought it was important to include though, because it puts into context the fact that a global atrocity like Munich did change awareness of the situation between Palestinians and Israel. But I’m also well aware that the Guardian has faced accusation of anti-semitism itself, that sites like CiFWatch have been set up to patrol that issue, and that the Guardian’s Readers’ Editor has not too long ago written about how the paper has not upheld its own standards.

There was also another reason to include it though. Written without the benefit of hindsight, Ezard concluded his article by pointing out how jumpy his office was about security.

“On the point of leaving I began to unlatch the main door with my left hand and decided to check that my press card had been returned to me. I half turned and dropped my right hand into my bulging coat pocket with unthinking haste. For a moment, until the top of the card emerged from my pocket, the faces in the Mayfair office were a study in tension.”

Said Hammami was shot dead in that same office six years later.

In fact, this section of the book had the potential to become an unremittingly miserable tale of murder, bitterness, blame and recrimination, but then you also get to Atlanta. My chapter on 1972 actually ends in 1996, with Anki Spitzer Rekhess, wife of one of the victims, watching the opening ceremony of the Atlanta Games alongside her daughter, and 13 other Israeli children who lost a parent in Munich:

“I wanted the children to see why their fathers had been in Munich. It was an emotional moment when the Israeli athletes appeared. I have no shame in admitting that I cried a little.”

1996 was the first time a Palestinian team competed at the Games. On the reaction of the children when they saw the first Palestinian team to compete in the Games enter the stadium, she said “I was proud of them. I did not know how they would react but they told me that they were athletes just the same as our husbands and fathers had been. When the team appeared in the stadium we cheered. It was a moment of reconciliation.”

On a personal note, I still believe it to have been an absolute disgrace that the IOC allowed some nations to refuse to have their flags flown at half-mast during the memorial service in 1972.

...and then move on to the Nazis

I found editing the chapter about 1972 emotional, and the one about the 1936 Nazi Olympics hard too.

You grow up getting taught an idealised and simplified version of how Britain and America saved the world from Nazi tyranny, and then it was a horrific discovery about what had been happening at the death camps when they were liberated.

But going through what was reported about Germany in the pages of the Manchester Guardian in the run-up to Olympic Games, you cannot help but come to the conclusion that Britain could have done more, sooner, about the plight of “non-Aryans”. And that we sent a team to that Olympics knowing full well about the humanitarian abuses that were going on under Hitler.

I included a letter to the editor simply signed “E.A.” and published in the paper in May 1936, pleading that Britain should not send a team to Berlin:

“Subscriptions from the public are being asked towards the expenses of sending a team from this country to the Olympic Games to be held in Germany this year. For Great Britain not to take part in this world competition would be a disappointment to many besides the intending competitors, but I am wondering if it would not be in the finest traditions of our ‘sporting spirit’ if on this particular occasion we refrained. [I] suggest that people who have money to spare might do better to relieve the desperate need of the [Jewish and ‘non-Aryan’] exiles and the oppressed than contribute to that which would support and encourage the present regime in Germany”

I also reproduced a lengthy article by a “Special Correspondent” (bylines were often anonymous then) sent from inside Germany in June, which leave nobody in doubt about the plight of the Jewish population in Germany at the time of the Olympics:

“More than three years of constant propaganda, suggestion and intimidation have begun to create a widespread anti-Semitic mentality such as never existed before in Germany or perhaps in any other country. Day in day out the Jew is represented as the embodiment of every evil, so that to refrain from taking part in the persecution, or to remain passive when the opportunity to persecute arises, is to be condemned as a ‘bad German’.

In this way an invisible Ghetto has been created which, just because it is is invisible, affords no protection as the gates of the mediaeval Ghetto did. The invisible walls are closing in on the Jew, edging him out of the smaller and remoter towns and herding him into the big cities, though even there he only has a respite, for little by little the entire Jewish community is to be destroyed.”

The ‘N’-words and newspaper archives

I saw a first draft of the Guardian’s ebook about the history of jazz, and my eyes nearly popped out of my head on the tube as I started reading content written in the 1920s that had no qualms about using the n-word. I studied history, so I am used to judging and interpreting language by the standards of the time, but there is something very raw about seeing it reproduced in the modern context of the Kindle, where somebody could be leaning over your shoulder thinking “What the bloody hell racist crap is he reading?”

Aside from that jarring experience, as a publisher you now also have to consider how that sort of language sits with the editorial policies of companies like Apple and Amazon who are going to be distributing the ebook.

For the Olympics book I had two specific problems. One was the occasional use of the stronger n-word as an adjective - for example in the 1948 opening ceremony, the Portuguese costume was described by one Manchester Guardian journalist as “n_____ brown”. That is straightforward - I would always edit that sort of reference out for a modern audience.

The second ‘N’-word problem is more nuanced.

‘Negro’ was frequently used in the paper in the thirties and forties to distinguish African-American athletes from their white counterparts on the US team. There are a couple of pieces that I found in my research that I didn’t include in the book, which specifically debated whether the ‘negro’ athlete was superior to the white athlete.

As an editor, though, the problem is that you can’t just shelve everything featuring that word as awkward, since you know you are going to have to use the word ‘negro’ in the book as one of Tommie Smith’s most powerful quotes includes it.

“It is very discouraging to be in a team with white athletes. On the track you are Tommie Smith, the fastest man in the world, but once you are in the dressing rooms you are nothing more than a dirty Negro.”

In fact the book contains some very powerful quotes about racism and sport. None more so perhaps than this from Jean-Claude Ganga, Secretary-General of the Supreme Council for Sport in Africa, talking in the seventies about Apartheid-era South African offers to compromise with specially selected mixed-raced touring teams and squads:

“Do not take blacks like monkeys to the show, and when it is finished, send them back to the jungle.”

My heart goes out to Zola Budd

South Africa is a theme that recurs in the book, and it is the hasty passport issued to Zola Budd in 1984 by a British Government under pressure from the editor of the Daily Mail that is one of the main features of the 1984 Games. My heart goes out to Zola Budd, who found herself caught in a political storm that was not of her making, and which ultimately prevented her from fulfilling her athletic promise. In her autobiography she describes the race in January 1984 where she smashed the 5,000m world record by more than six seconds, and which brought her to the attention of the world, as “probably the worst day of my life.”

This is a book, not an anthology of articles

As I’ve mentioned before, when editing these books compiling newspaper articles, you have to do a lot of re-work on them. Including two or three articles on the same topic often leads to the original draft having a degree of repetition in it. You don’t need - as a daily newspaper article usually does - to mention that Avery Brundage is President of the International Olympic Committee every single time he crops up in the book.

And tone has to carry across from section to section. My original blog post about Munich was rather scathing at the speed with which the US and Soviet athletes recovered from the terrorist attack on the Games, to take part in a bitterly contested basketball match, which they began talking about in terms of life and death. I’ve put Sean Ingle’s brilliant retelling of the tale into the book, but had to edit it a little for tone. In my book it comes almost immediately after a report of Israel receiving the bodies of their fallen athletes, and so Sean’s use of phrases like “being stiffed” and “to the grave”, which are fine in the original piece, don’t work anymore in that context.

The power of people

People’s own personal experiences are one of the best ways to tell history - and with the benefit of the Guardian archive there are some great stories in the book. There is a powerful piece by Lord Philip Noel-Baker, an Olympian in 1912 and 1920. He wrote for the Guardian about why, many years later, he regretted personally choosing not to attend Hitler’s 1936 Games: “My self-sacrifice in not going to Berlin served no useful purpose. It did Hitler no harm, just as my presence would have done him no good.”

Equally powerful is Hugh Matheson, explaining why he has chosen to attend Moscow in 1980 in the teeth of fierce pressure from the British Government not to go:

“In a divided world in which the Western leaders ignored both the constitutional realities of the sporting organisations and the aspirations of other nations, it was an extraordinary political error to call for something which could not succeed. The partial boycott is without point, particularly when, without exception, the banned athletes that I have spoken to are disgusted by the methods used to secure the limitation of their freedom.”

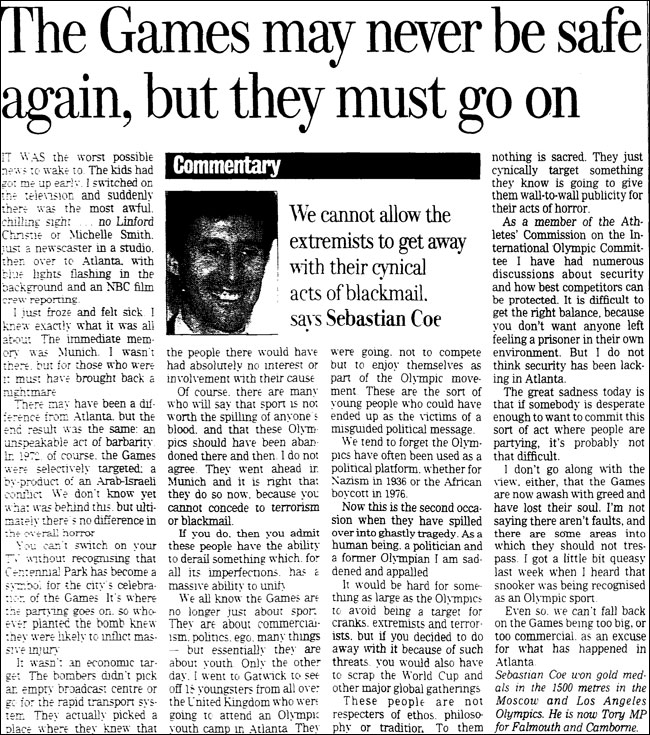

There is also an emotive Observer piece by Sebastian Coe, at that point a Conservative MP, on his reaction to the Atlanta bombing, and why the Olympic Games must continue:

“Of course there are many who will say that sport is not worth the spilling of anyone’s blood, and that these Olympics should have been abandoned there and then. I do not agree. They went ahead in Munich, and it is right that they do so now, because you cannot concede to terrorism or blackmail. If you do, then you admit these people have the ability to derail something which, for all its imperfections, has a massive ability to unify.”

Sebastian Coe in the Observer in 1996

Too big. Too expensive. Too commercial. It has always been this way

I loved being in the Guardian’s digital archive, and seeing that all of the complaints we hear about the London Olympics have been done a million times before. In 1896 the Manchester Guardian was reporting that Athens had little chance of getting the track ready in time due to bad planning. In 1936 an emergency decree had to be passed to stop people turfing out long term tenants and letting out their Berlin flats at exorbitant rates whilst the Games were there. In 1948 the Finnish Olympic Committee were embroiled in a scandal when they were caught re-selling their tickets. In 1964 the Japanese were accused of over-elaborating the opening ceremony and over-doing the Olympic branding everywhere. In 1996 the Guardian carried a two page spread about how the commercialisation of the Games in Atlanta had gone too far.

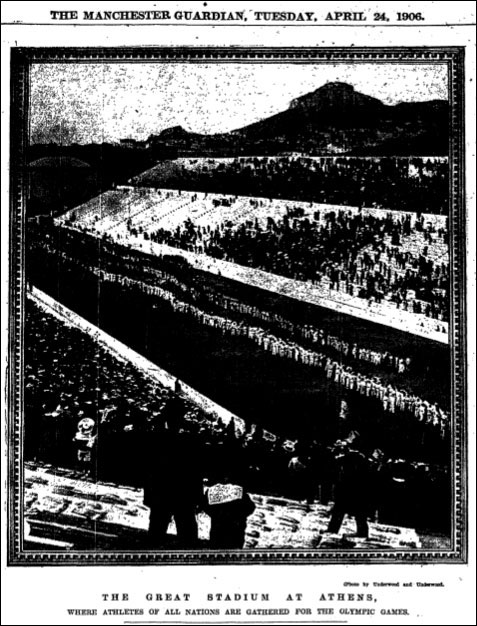

Manchester Guardian coverage of the 1906 ‘Intercalated’ Olympic Games

Keep feeling fascination

In the end though, all these things are the reason why the Olympics fascinate me. Somehow, through the medium of having a global sporting event every four years, the controversies that surround the Games actually tell the story of the last century-and-a-bit. Gender and racial equality. The rise of fascism. Terrorism. Human rights. Animal rights. Cold War stand-offs. Globalisation and the rise of corporations over nation states. It is all there.

“Keeping the Torch Burning: Terror, Protest and the Games” is an alternative history of the Olympic Games, one that focuses on the social and political events that have defined each competition. Nationalism, separatism, feminism, racial equality and human rights ring loud in this Guardian Short, written by Martin Belam and uniquely told through first-hand reporting from the Guardian and Observer.

“Keeping the Torch Burning: Terror, Protest and the Games” - £2.99 on Kindle