How digital transformed the news cycle - and what you can do about it

I always assumed I’d get away without speaking at a London Hacks/Hackers gathering, since I fall into neither camp.

I’m not a hack, although I often get mistaken for one, or people at least assume I have a journalistic background. I do write a lot, but I’ve never considered myself a journalist at all. I think my “news sensibility” comes from having spent a long time in media organisations, and from my study of history. I always think that is never a million miles away from journalism - trying to understand a complex set of events via multiple sources, working out which of them is spinning or lying and why, and then making it all easy to understand for a non-expert audience. And the great thing about being a historian is that dead 13th century saints don’t tend to spam you with press releases.

And I’m not a hacker, either. Again, people often assume I am. I can program - I learnt BASIC on a BBC Micro and used to have a ZX Spectrum, and some of my shonky Perl even got used in production systems at the BBC, but my interest is in how humans interact with computer systems, not how computers work themselves.

For the last few years my fascination has specifically been how journalism and technology and audiences come together to enable story-telling, and the transformation that brings to the organisations that deliver news. And so I guess, in the end, it was inevitable I would do a talk there...

At Hacks/Hackers London I presented eight things that I believe news organisations need to stop doing, start doing, or do better, in order to cope with the way that digital has transformed the news cycle.

(And on the night, with my tongue-somewhat-in-my-cheek, I suggested that when I said “we” in a good context, I meant “we at the Guardian”, and when I said “we” in a negative context, I meant “we in the news industry as a whole”)

The content life-cycle

I started with a rather crude view of the traditional content cycle for a print newspaper: 1) Write newspaper. 2) Print newspaper. 3) Wrap fish‘n’chips in the newspaper.

Now, I’ve missed out some vital steps there.

Before they’ve all been used as chipwrapper material, you have to remember, for example, to send a copy of each issue to the British Library. And, in the Guardian’s case, to our own library, as we are one of the few newspapers globally to still have a room on-site with books and librarians and archivists.

And there have been some changes at the printing stage. You need to remember to send an image of the following day’s front page to @suttonnick so he can publish them to Twitter with the #tomorrowspaperstoday hashtag. And publish everything to the web.

I have also, it must be said, simplified the “write newspaper” step. I sort of missed out: sub-edit it, check it with legal, write the headlines, clear the rights for the images, make late changes, re-sub it, syndicate the best bits, and get the files packaged up to go to the presses correctly. And many, many, many other steps that I’m ignorant of.

In fact, I often joke that if the Guardian put me in charge of all things digital, then the website would carry on swimmingly. If, however, they put me in charge of all things print, the paper would fail to come out the next day. That isn’t true of course, because the print operation is so tightly rehearsed that everyone would get the paper out on time despite my inept buffoonery at the helm. It would just probably have more coverage of Kraftwerk in it than usual.

But along the way there, I casually dropped “and publish everything to the web” into the list of steps. It is this which has changed everything over the last 20 years, and why news organisations need to adapt.

1. Stop the shovels

Mobiles are not tablets. Tablets are not desktops. And neither of these things are print products.

It worries me that the rise of mobile apps and tablet devices is causing Shovelware 2.0, as people rush to publish all of their existing content on these new platforms and devices without considering the new formats that might be required. An iPad app that simply displays a PDF version of the layout of the print edition of a newspaper is not utilising the form of the device.

I’ve said before that we are in “the animated gif years” of design for tablets and smartphones. It is very early days to have settled down into established design patterns and visual conventions.

And for those of you young enough to be wondering what I mean by “the animated gif years”, it is my solemn duty to inform you that the internet used to look like this:

As an industry, we currently seem to be trying to pump out all of our content, on all of our platforms, regardless of whether it is suitable. A recent brilliant Telegraph interactive showing before and after photos of damage caused during the London riots urged users on the iPad to interact with it using a mouse, and the Guardian produces some interactives that render as one apologetic line of text if you are using an iOS device that refuses to run Flash.

At the most basic, any text that says “(See diagram left)” fails to take into account the fact that the positioning of the diagram might move around according to the orientation of the device. Little cues like that tell the reader that you haven’t really made that content for them and the way they’ve chosen to consume it.

See also: A good read on making news native on touchscreen devices: “A short way down the digital road” by John-Henry Barac

2. Be fast

Armed with little more than an iPhone and the Tumblr app, from a standing start, most people can publish to the web faster than most journalists or reporters could get something live on their organisation’s website. There are some sound reasons for this - tech security and the need for a second pair of eyes amongst them - but given that our industry is all about publishing, this makes us look slow.

(On the night of the Hacks/Hackers talk, Twitter was awash with the news that Fenerbahce had been withdrawn from the UEFA Champions League, and there was a lot of discussion as to the implications and who might benefit. The BBC, Guardian and UEFA websites at the time had not a mention of it, even as a “Breaking” strap)

This speed gap is being emphasised with print even more and more. I still instinctively look at the news stand as I walk past it on my commute to work, and after a couple of seconds, I remember that I saw all of the front pages the night before thanks to @suttonnick and other sources. By the time I’m at the point of potentially purchasing a paper, I’ll have watched some morning TV news, and checked the news on my phone. And the papers are still featuring front page stories that I first saw ten or eleven hours previously.

Speed isn’t everything - I was gently reminded by more than one person after my talk that this section should maybe be called “Be fast and still be accurate” - but the fastest emerging way of reporting digitally is the live blog format. I’ve argued before that it is our first “native” digital news format. You can print out articles, you can broadcast podcasts on radio, and stick video reports onto the telly. It is very hard to reproduce the live blog in any format other than a digital screen.

If you look at the Guardian’s minute-by-minute page, you’ll see us covering a wide variety of topics - sport, television, politics, world news, the NHS - in this format. I’m not sure that “live blog” is always the right strap for them, but it is a very flexible format that has been adopted to one extent or another by most major news providers.

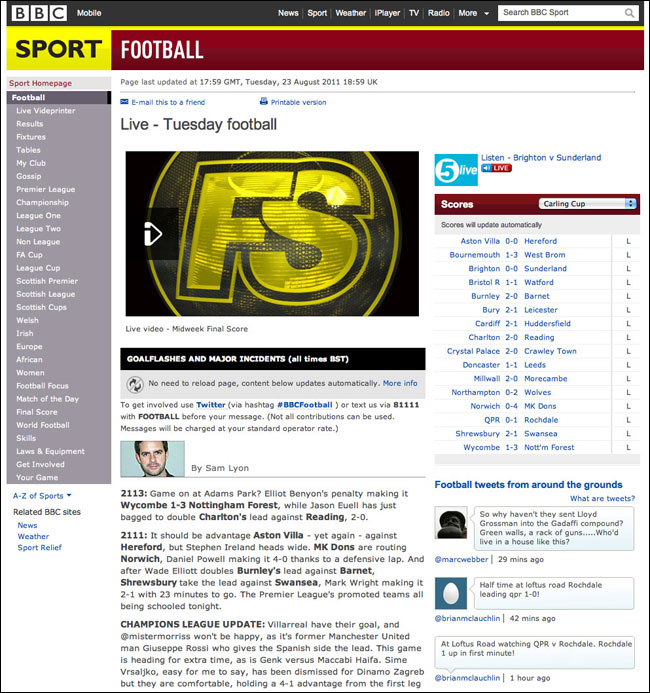

Rather like the tablet and smartphone, I still think the information design and visual presentation has room for improvement. At the moment, I’d argue that the BBC has the best set of tools. Their Carling Cup live page last Tuesday featured video, text updates, tweets from around the grounds and the latest scores. All were updating independently from each other.

And new story-telling tools are appearing all the time. DocumentCloud, for example, can be usefully used to annotate source documents and present them to the user. Storify seems to be the darling of the moment - see Mary Hamilton’s Storification of this talk, my coverage of a bunch of idiots marching in Walthamstow, or this local news site capturing condolence messages for a fallen police officer.

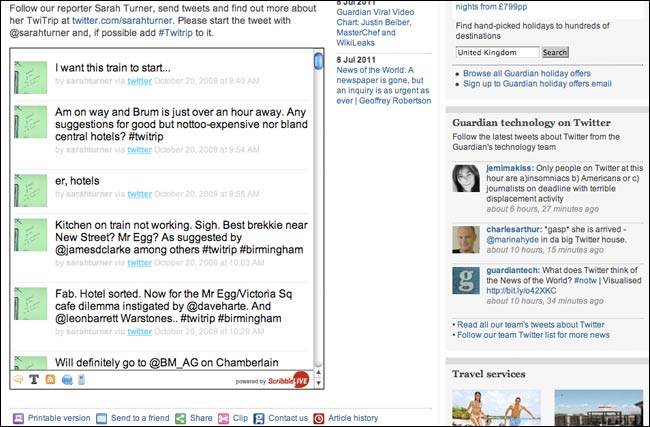

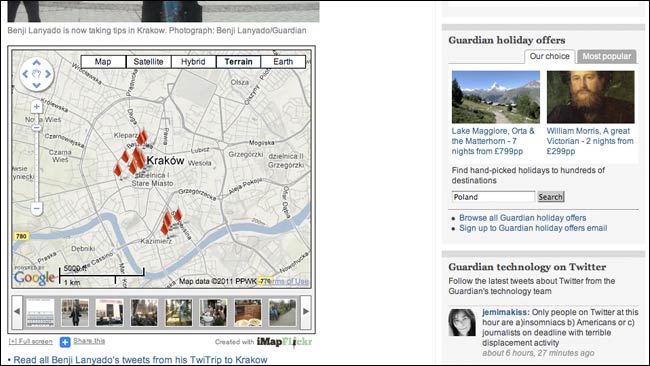

I think it is really important that journalists are allowed to experiment with these new formats. At the Guardian Benji Lanyado has made his name with his #TwiTrips, where he visits a city and gets people to point him in the direction of the hidden gems via Twitter. He discovered it by accident when he asked what to do once when he was stuck in Berlin with a few hours to kill, and ended up getting a tip from a local to go to an amazingly cool coffee house that would never appear in any guidebooks.

“Live” pages for TwiTrips on the Guardian website

In the Guardian CMS we have the dangerous “embed object” button. It effectively allows any journalist the ability to add any HTML code to any article. There is a huge risk there, but it also means that as soon as any new service appears on the web with an “embed” button, our reporters and staff can start using it.

(On the night, I did also suggest that the masked out buttons in the image were even more dangerous options like “initiate self-destruct sequence” and “sack the editor”)

On the recent nights of rioting in England, Paul Lewis seemed to be building on Benji’s technique, and carrying out a sort of riots #TwiTrip, asking for verified reports of trouble, and then racing off to cover them. It was a fascinating way of trying to use social media to help direct the reporting of an unfolding story.

See also on this blog: Benji Lanyado on TwiTrips and technology at the Guardian

The Guardian’s Paul Lewis on crowd-sourcing investigative journalism with Twitter

Verifying social media in the middle of Egypt’s revolution

3. Be permanent

As Emily Bell has observed, the news cycle is not only getting much faster due to digital publishing, it is simultaneously getting longer. Much, much longer. In fact, in theory, web pages could live forever.

On guardian.co.uk, for example, we still have our Euro2000 site up and running. Whilst it is great to still have this content available, it also carries overheads. Those pages are running off a legacy CMS which we have to keep going in the background, or we have to chose to migrate or kill the content.

Permanence poses a journalistic problem, as well as a technical one. In the days when the paper got thrown away and only a few copies persisted in libraries, the accuracy or not of a particular piece several years earlier was still important, but less pressing. With permanent web pages and Google, a story might suddenly return to the public eye every quickly.

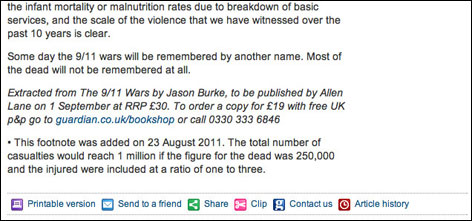

As an industry we need a better approach to digital corrections. I do like to think that one of the reasons the Guardian has a reputation for making more clumsy errors than other papers is because we are simply more up front about admitting it. On any given day, our corrections column will contain a list of trivial and not-so-trivial errors, and notes of those errors are appended to the foot of the original article. We tend not to “silently” correct anything except the most basic of typos.

There has been a frequent argument that news sites should keep every version of a story, so that there is a transparent audit trail of changes. I’m not a fan myself - I think this is overkill. It also doesn’t take account the fact that often, when you make changes for legal reasons, you need to remove the offending content from the web, not just hide it behind a button saying “see previous versions of this article”. Newsniffer attempts to document every change to BBC News, and a quick poke around will reveal that the vast majority of these changes are rather dull and insignificant. For me a full-on Wikipedia-style “diffs” approach would be too much for a news site.

As an industry we also need a better handle on how to gracefully “disappear” content that works with the rest of the internet. Deleting an article also means trying to get it removed from search engine caches, and sometimes our HTML betrays us. In one instance, I spotted an example where the significant element of a story had changed - it turned out the presence of names on a terror watchlist was a coincidence - but the HTML title and URL still made the accusation: “Names of two passengers on doomed Air France jet linked to Islamic terrorism”

Perhaps the most glaring example I’ve ever seen was when the Mirror had to withdraw a story because it breached a court injunction, only for the URL slugwords appearing in the 404 page they replaced it with to keep repeating the headline.

4. Organise and own

In print, a newspaper has a minimal amount of “furniture” and “peripheral” content. You might have a regular publishing imprint, and a list of contact numbers and addresses, and details of how to subscribe and get back issues. Online, the amount of peripheral content that gets generated for a website can be staggering: help text, privacy policy, terms and conditions, FAQs - the list goes on and on.

Left: An article from our science section. Right: Our search help text

And there is a real contrast between the care applied to these different types of content. A science article will have had several pairs of eyes on it. The search help text was written by me on a wet Wednesday afternoon, and I’m not entirely convinced anybody apart from me, including our users, has ever read it.

Last Wednesday I showed a screengrab from our CMS of a help page on the Guardian website. In the notes it says the page belongs to Martin Hearn, and he needs to be consulted before there are any changes. Martin left in February April. This example is typical of what happens when a website has some “second class” content.

In order to keep these types of pages accurate and useful, news publishers need to adopt a “web governance mindset”. Content audit spreadsheets may look like one of the dullest things that IAs or content strategists ever do, but they are incredibly useful. You should have an audit of all of your “peripheral content” pages, with titles and URLs noted, owners assigned, and dates for when the pages need to be checked.

See also: “Doing a Content Inventory (Or, A Mind-Numbingly Detailed Odyssey Through Your Web Site)” by Jeffrey Veen

“Resource — Content inventory spreadsheet” by Donna Spencer

5. Metadata is your friend

Online, content eventually lives and dies by the metadata applied to it. Metadata frequently governs how material features within your browse structure, and elements like the HTML <TITLE> tag will determine how attractive a listing is in search results. A key metadata feature of the Guardian’s CMS are tags - and keyword manager Peter Martin & myself wrote an extensive series exploring our tagging for the Guardian Developer blog entitled “Tags are magic!”.

A new breed of metadata is appearing on the web - semantic mark-up. There are various ways now of helping computers understand, when faced with a document, exactly who the publisher and author are, when an article was published, and the topics it covers. News organisations should be considering how this can be used to their advantage.

With the bonus that the future will thank you for marking up your content properly.

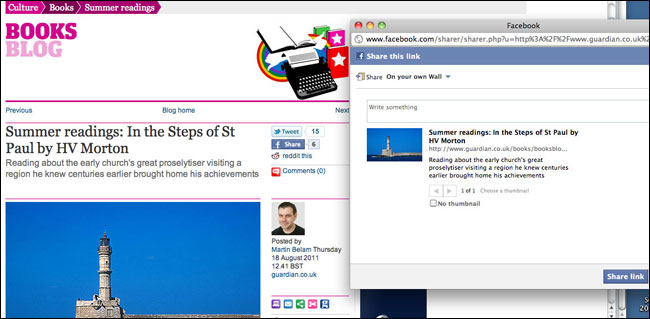

At the Guardian we’ve recently implemented Facebook’s Open Graph metadata on our article pages. This isn’t because it is the best format, but because it is one where you can make a quick and compelling business case. The Open Graph metadata is lightweight to apply, and hides in the <HEAD> of your HTML document. Any template-based CMS ought to be able to produce the correct output easily. As a publisher, it allows us to control what appears when people press the “Recommend” button on our pages - picking the best image, headline and description text to appear within the Facebook ecosystem.

And there are plenty of other flavours of semantic mark-up available.

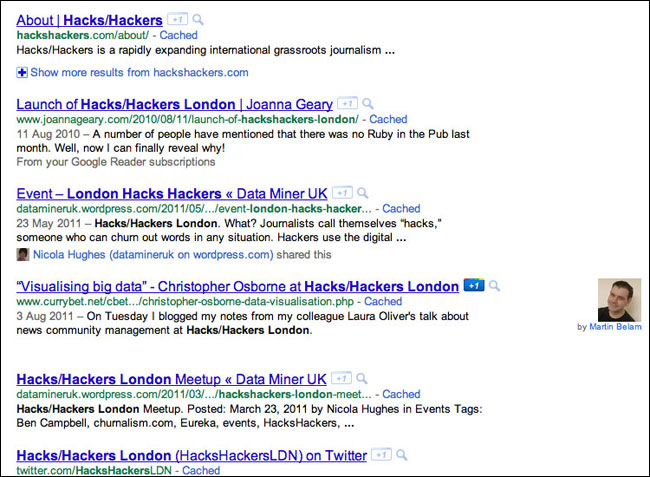

Google recently introduced a way of marking authorship on web pages, and now displays the authors byline picture next to an article in search results. It isn’t the most elegant design but I expect it has been tested to prove that the human eye is drawn to faces, and this increases the attention paid to those particular results. At the moment, until everybody has done it, getting Google to display your content this way may give you a slight advantage in search engine results.

And that still leaves schema.org, rNews and existing microformats as ways that you can improve the machine-readability of your content.

6. Curate

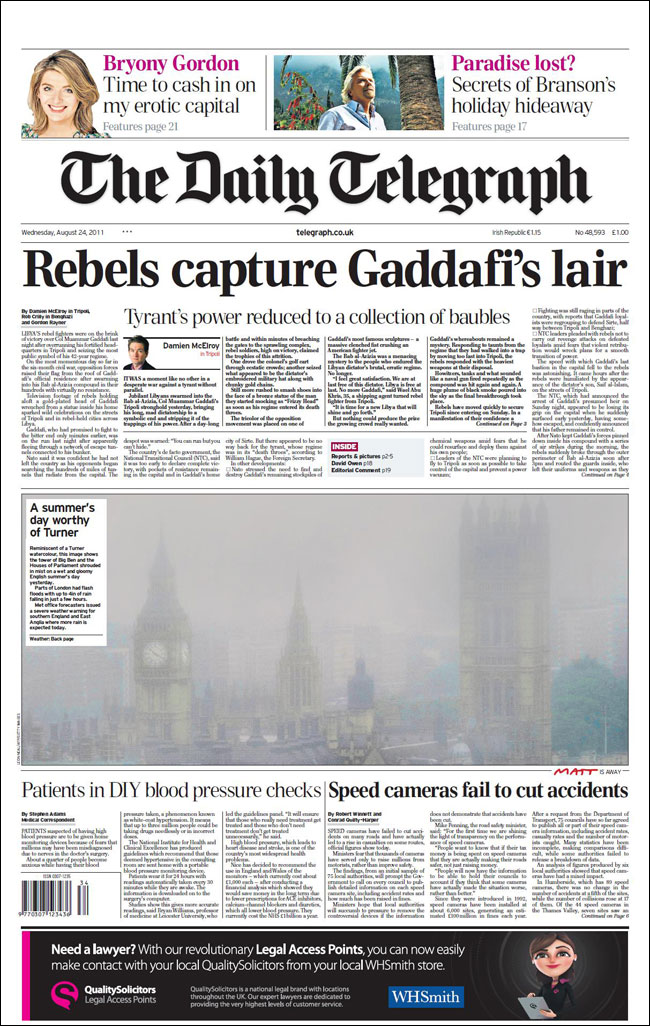

Not all news content is born equal, yet very often it is difficult to reflect that on a news website. If you look at the front page of a paper, the visual hierarchy often makes it abundantly clear what the main stories are.

On this Telegraph front page, for example, you can see that whilst the picture dominates the page, the story it belongs to is small, with a tiny headline. The main story is at the top, and there is even a differentiation between the two stories at the bottom. The one of the right, which features a “continued on...” trail, has a bolder font in the headline. Online though, I’d wager that all of these stories, with the possible exception of the image, will use virtually the same template.

As an industry we need to get better at signalling context online and within digital products.

This can often be seen on the more serious news websites, when anything less-than-absolutely-serious is published. A recent example on the Guardian was a piece where Sali Hughes talked about the message Cheryl Cole might send out to young girls who regard her as a role model by taking back a husband who had, allegedly, been unfaithful. The comment thread underneath was filled with spluttering indignation that the Guardian might publish such a thing - “do you call this news?”.

Sali herself made one of the best interventions into a comment thread I’ve ever seen an author do - and it is well worth reading in full. It can be summed up with this quote:

“I suppose what I find most baffling is the unadulterated rage expressed by readers who’ve chosen to read a celebrity column (in a sea of more serious comment), then become enraged that it’s about celebrity. It’s like reading a gardening column and feeling aggrieved that there’s mention of flowers and plants. The Comment section is packed with columns on world and domestic politics, social issues and other weighty subjects. This is one column on a subject some of you happen not to be interested in. You seem to assume that the Internet is this finite resource, on which I am taking up rare and precious space with my offensive fluff. What did you expect when you clicked on it (for free)?”

Part of the issue for the reader, again, is that the article appears stripped of context - in the same template as a leader article or comment pieces on more “worthy” topics.

Topics that, incidentally, will probably have less impact on the behaviour of young people than Cheryl Cole’s behaviour does - a fact that will still be true even if you wish to close your eyes, stick your fingers in your ears and trill “La-la-la celebrity culture in the UK does’t exist” until you are blue in the face.

In the design of our pages, we increasingly try and give little signals to help improve that context for the reader. For example, comment pieces have a little byline picture next to them when listed on an index page or front, and news pieces do not. It is just a small cue to indicate “this is written by this specific person and represents the views of this specific person” versus “this is the news.”

Comment pieces with byline pictures on the left, news pieces on the right

News organisations also need to make it easier for people to find the best of their content. If all news content is not equal, then it follows that not everything you’ve ever written on topic x is of equal value. The strictly reverse chronological ordering of most news sites treats all content as equal.

On the Guardian site, we have around 9,000 topic pages automatically built by our use of tags. For some, like Maternity & Paternity Rights in the Money section, we use a standard template that automatically calculates some related topics, and displays articles and blog posts in reverse chronological order.

Our CMS, however, allows us to override the default template for tags of high interest. Our “phone hacking” page has been - I’m sure you can imagine - the subject of much editorial love, and so features a full three column layout, and plenty of custom “trail-blocks” to allow editors to highlight the really key articles and documents.

See also: “The tyranny of chronology” - a presentation I gave at a ‘News Innovation’ unconference in London, July 2009

7. Expand and re-use

News has been recorded by newspapers for, literally, centuries, and our collective archives are a unique proposition that we should be making more of. I love, for example, the Times Archive blog, which is, for me, worth the price of a Times digital subscription alone.

This is a resource the like of which very few companies have access to. As well as monetising the archives themselves directly by charging for access to them, increasingly news organisations should be looking at how they can re-purpose this resource.

With Guardian Shorts, we have just started to look at how our topical content can be quickly turned into ebook “backgrounders”. Our first title was issued in August - “Phone hacking - How the Guardian broke the story” - and there are several more titles in the pipeline. The idea is to retail them for between £1.99 and £3.99 for Kindle and the iBookstore.

They do take a bit of work however, and expose one limitation of the news medium. I am editing a title for the series myself, and have meticulously scored out from the manuscript the same establishing paragraphs over and over and over and over again. In print, we always seem to assume that the reader has understood virtually nothing of a story previously or is coming to the topic fresh, and that they have no other reference materials to hand. Digitally, of course, they may be coming to the topic in ignorance, but they have an abundance of reference materials just a click away.

8. Don’t stop learning

Those first seven points were going to form the entire basis for my talk, until the day before I gave it, when this article was published by the Press Gazette. I’ve already blogged specifically about it, but I’ll incorporate some of that into this essay, since it formed the basis for what I said at Hacks/Hackers.

The Press Gazette piece suggested that today’s editors do not value education in digital media skills.

“The top four most important skills cited by editors were: writing, finding news stories, interviewing and legal knowledge - while at the bottom of the list came social media, web skills and interaction with readers”

When I read a sentence like that, I hear the sound of an industry committing suicide.

Now, if you actually dig into the details of the survey, you’ll see it wasn’t that these skills aren’t valued at all, but that were valued less than “time management” amongst other things. Alison Gow blogged eloquently about the message that sends out to existing digital staff in the UK’s newsrooms.

What concerns me is that there are a whole generation of students who are being encouraged to pay for qualifications that will equip them to work in a 90’s newsroom, because the people designing the courses and the industry input they receive are all from people who cut their teeth in a 90’s newsroom.

Surely the aim of this type of qualification should be to address the skills gap in our industry?

If you get a job in a newsroom, you will be surrounded by years of experience in “traditional” journalism. What you won’t generally have is frequent access to people with the digital skillsets the industry is transitioning towards.

And in our industry we are still getting so many of the digital basics wrong. There is no way that I would dream of writing a piece on this blog about a survey or a news article and not link to it, yet that Press Gazette piece doesn’t link to the source. It baffles me that this is still considered acceptable by a digital publisher in 2011.

And once you’ve been made to do your own research to get to the original survey, the NTCJ page in question commits one of the most basic usability errors you can make. At the foot of the article it says “You can download the full report by clicking the link on the right.”

Because, as a user, I really want to be directed to hunt around the screen to find the link, to save the content producer the bother of actually adding a hyperlink into their text.

And they say better web skills aren’t a priority for our industry...

Despite all this, I’m still optimistic

Earlier this year, journalist and entrepreneur Rick Waghorn leaned forward to me in the pub, and whispered conspiratorially, “Martin, are you confident about us?”. And by us he meant the news industry.

“Yes” was my answer, for several reasons.

Actually, I think “legacy” media companies are still well placed in a digital world. We retain mass audiences, and we have established brands that stand for particular values. There are very few genuine entrants into the market that carry equivalent reputations or the power of endorsement that our old news brands do. People still say “He reads the Telegraph” or “Typical Guardian reader” in a way that they don’t say “She’s a HuffPo user” or “That’s such a Yahoo! News thing to say”.

The media business landscape will look very different in three years times, five years time, and ten years time. We’ll inevitably all go through a painful process, because I think media businesses will be much smaller commissioning and curating houses, rather than big content-production factories. But people love stories, and they love gossip. They love reading them, watching them, and listening to them. A reshaping of the business model is inevitable, but the demand for news, entertainment and political accountability will ensure that there is a business model to be found.

And, as I posted last week, the quality of young talent coming into journalism makes me optimistic. At the Guardian we have hired a brilliant crop of young digital journalists in the shape of people like Laura Oliver, Hannah Waldram, Hannah Freeman, James Ball, Mary Hamilton and Josh Halliday. I see things like the data work of Conrad Quilty-Harper at the Telegraph, or the fact that Joanna Geary at the Times has got Hacks/Hackers running in London, and it makes me confident for the future.

What does concern me though is that throughout the media industry, in both print and broadcast, I worry that there is a layer of senior and middle management who are allowing their companies to coast into decline in order to protect their own salaries, share options and pensions, rather than take the hard decisions which are going to be necessary to turn those companies into successful digital businesses.

In the spirit of Chris Thorpe’s post about Young Rewired State, I think these people should gracefully step aside and give the digitally focussed people in their businesses the opportunity to shape the future that will ensure they survive long into the 21st century.

Acknowledgements and “We’re hiring!”

A big thank you first of all to Joanna Geary for inviting me to talk at Hacks/Hackers. I put this together at short notice with a very ambitious title, but it made me very quickly crystallise some vague thoughts into a series of bullet points. Secondly, thanks to Karen Loasby and Lynsey Smyth at the Guardian who had the patience to discuss this with me as I pulled it together.

Probably worth a timely reminder of the disclaimer on this website: This is my personal blog. The views expressed are my own, and do not reflect the views of Guardian News & Media Limited, or any current or former employers or clients. Read my blogging principles.

Oh, and finally, we’re hiring - there are a whole host of roles available in our technology department at the moment for product managers, project management roles and software developers too.

“Hacks/Hackers London: Notes from the talks” brings together notes from 16 talks, including those from Martin Rosenbaum, Stephen Grey, Alastair Dant, Scott Byrne-Fraser and Wendy Grossman. It looks at topics of interest to journalists and programers alike, including freedom of information, processing big data sets to tell stories, social activism hack camps, the future of interactive technologies, and using social media to cover your tracks - or uncover those of somebody else.

“Hacks/Hackers London: Notes from the talks” for Kindle is £1.14.

Some reaction to this post on Twitter:

@Cathy_Watson: "Lots of digital news expertise demonstrated in this @currybet essay but does it overlook the need to make money?"

@opensahara: "Best article on the subject in ages"

@davorg: "Love @currybet's 'the internet used to look like this' graphic"

@ThomNagy: “Another must-read piece by @currybet”

All excellent but a minor quibble.

Can I suggest "the quality of *new* talent coming into journalism" rather than "the quality of *young* talent coming into journalism"?

Fair point - although from my aged viewpoint they appear to be synonymous these days :-)

Good piece Martin, and very interesting. I would like to hear your thoughts on my current employer, huffingtonpost.co.uk . We're in the lucky position of not having to put out 'chip paper' each day.