“Come as you are” - Part 1: The Reckless years

I get asked a lot “How do you become an IA?” or “How can I get into user experience design?” And the answer is still, I believe, in lots of different ways. We are still a young industry, with maturing disciplines, and I don’t believe that there is a set career path to follow. You certainly wouldn’t look at mine and think that I’d got it from a careers advisor when I was 18. In fact, when I was 18, my careers advisor would have had to have been quite prescient, as Mosaic, the first web browser, was still a few years off.

Textbook career path or not, when I was asked to talk at the Polish IA Summit, I’d recently been to an event in London called Lightning UX, where ten presenters give five minute “lightning talks” each. One of those was by Boon Chew, and he was talking about the career path that had taken him from being a software developer to being a UXer. In the course of it, he said that when he had been looking to get into UX, there weren’t that many personal stories out there for him to read to see how other people have done it.

So I thought for my keynote talk I’d walk through examples of some of the work that I’ve done over the last thirteen years of making websites and digital products, looking at how I think they represent not just the story of my career, but how the discipline of IA has evolved over the last decade.

And I’m going to finish by listing what I think are the five key things you need to do in order to have a successful career as an Information Architect.

Now one of the things that we have to face collectively as IAs is that we can tend towards the nerdy, geeky, obsessive type of personality, and if you get a bunch of book-ish IAs together, it won’t be long until the topic turns to how you organise your bookshelves. Or in my case music.

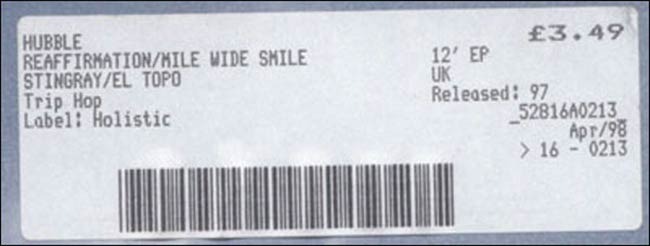

I used to have an elaborate filing system that involved having everything I owned in a set order, based on the relative chronological order of releases, in an overall alphabetical framework. There was a strict ruleset on how limited edition, import and promotional releases fitted into the chronology. [1]

It was because of that obsession with music that I ended up working in a small record shop in Walthamstow called “Note For Note”, and then, after University, found myself working for Reckless Records in Soho. At the time it was one of, if not the best known second-hand shops in London, and even if you have never visited it, you may be familiar with it, as it appears on the cover of the Oasis “What’s The Story Morning Glory” album. When I was working in the record shop, I was doing three things that I would now consider to be comparable with what I have done over the last decade as an information architect.

Classifying content for the audience

The first was correctly classifying and labelling content for the end user. “Bleach” by Nirvana would sit in U.S. Indie. A niche album by a niche band. “Nevermind”, or the other hand, belonged in “Rock/Pop N” - a radio friendly unit shifter indeed.

Selling music successfully in physical retail spaces meant making sure that titles were placed where customers were expecting to find them. With a band like Nirvana, you would get to a point where their releases would no longer sell from the U.S. Indie section, because the “too cool for school” indie kids would consider them a sell-out for having signed to Geffen. And the kind of customer who might have heard “Smells Like Teen Spirit” on BBC Radio One expected to find them amongst the mainstream. Or in other words, correct content classification was vital for improving conversion rates.

Adapting systems to make them easier to use

At Reckless we had a UNIX-based stock control system. It was an unwieldy beast, and was not especially suited to purpose. For example, a data record on an item would have about 35 fields to fill in. In the shop we only used about 10 of them, but you had to hit enter and put in blank data for all of them.

The price stickers we used reflected the structured data in our stock system

These kinds of things slowed down data entry and processing new stock. One of the things that I was involved in was proposing changes to the system that sped up the tasks we used. The data entry pattern was altered to skip over fields we didn’t use, for example, and a search by EAN was added, so scanning the barcode of a CD would save staff having to type.

I was making suggestions of how to optimise a system for the end users, by observing the tasks they struggled to perform well. Sound familiar?

What I didn’t realise at the time, although I do now, is that much of the problem with the software was that it was using the wrong information domain model. It had originally been written for use in library cataloguing, so the underlying logic of the system was always based on what would work for books, not the domain model of music releases.

Dealing with data

By 1998 we had a fledgling website, and we were trying to list our current stock on the web so that people could buy mail order. We already had a Rarities department that took classified ads in Record Collector magazine, but we wanted to offer a broader range of stock. There was an export script that I had to run, which generated some CSV files, and I then had to process them in Lotus 1-2-3 to wrap them in some rudimentary HTML, before adding the listings into some Dreamweaver templates I’d made, and FTPing them up to the web. Now that sounds like a horribly convoluted process that you wouldn’t wish on your worst enemy, but that is how the web was for a small business back then.

What was frustrating, and an issue I still have to deal with today, was the data quality. On the one hand, staff had no incentive to enter correct metadata, they were incentivised to process stock as quickly as possible, not as accurately as possible. On the other, the people writing the export script had never seen the HTML templates I was using, so the export wasn’t in quite the right format. So I used to spend a couple of hours cleaning the data, and working out which problems needed to be corrected by changing the stock record in the database, which problems could be corrected by writing macros in the spreadsheet software, and which needed the software provider to do some work on the export script.

Next...

In part two of this series I’ll look at the IA-like work I carried out at the BBC in the early 2000s.

[1] Incidentally, the last time I blogged about my obsessively nerdy music habits, legendary NME journalist Swells called me “the antithesis of rock‘n’roll” on The Guardian website. Sadly he isn’t still around to insult this post [Return to article]