The Guardian's Paul Lewis on crowd-sourcing investigative journalism with Twitter

“What are the best ways that we can get people to help us in our investigative endeavours through the internet?” - Paul Lewis

Last week I attended an event at the Royal Statistical Society looking at data and news sourcing, and one of the panel sessions was about crowd-sourcing using the internet. My Guardian colleague and 2010 Reporter of the year Paul Lewis was one of those appearing, and he has been at the centre of a couple of investigations that have used Twitter extensively as a component of the research and reporting.

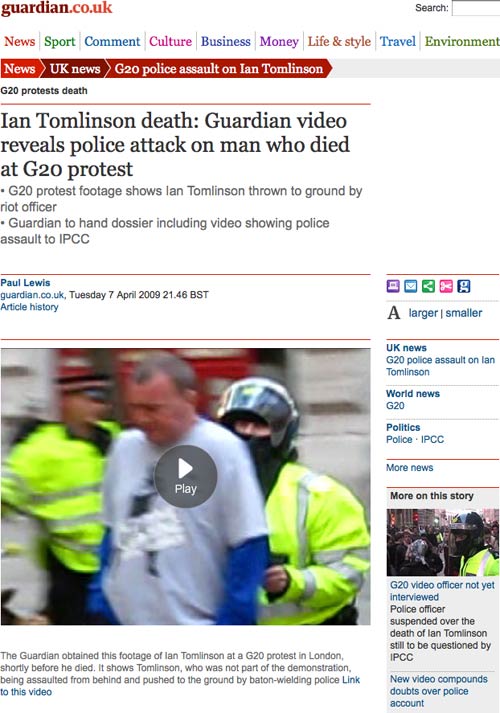

Talking about investigating the death of Ian Tomlinson at the G20 protests in London, Paul found Twitter to be “just the most remarkable tool in which to share an investigation”. He believes that whether he existed or not there would have been a motivated group of people on the platform who wanted to find out what had happened. It contained a crucial factor that makes crowd-sourcing a success - there was a reason for people to help, in this case a perceived sense of injustice and that the official version of events did not tally with the truth. Six days after Tomlinson’s death, Paul had twenty reliable witnesses who could be placed on a map at the time of the incident - and only one of them had come from the traditional journalistic tool of a contact number in his notebook.

Paul Lewis also used Twitter to aid investigating the death of Angolan refugee Jimmy Mubenga on British Airways flight 77. There, he said, the key skill had been in listening. There were a finite number of witnesses - the people who had been on the flight and who were close enough to see something. Following some questions on Twitter he received a phone call from a man in an oil field in Angola who said he knew something. From then on, traditional journalism took over, with Paul, for example, getting verification that the man was who he said he was, and had actually been on the flight.

Crowd-sourcing doesn’t always work, Paul said. The most common thing is that you try, and you don’t find the information you want. He thinks the pattern of movement of information on the internet is something journalists need to get their heads around. Individuals on the web in a crowd seem to behave like a flock of starlings - and you can’t control their direction.

Paul Lewis opened and finished with a note of caution. “The pitfalls of crowd-sourcing keep me awake at night sometimes” he said. He worries that journalists and news organisations are now more vulnerable to deliberately placed misinformation and propaganda than ever before. Verification is hard across the web, and the eagerness to break news leads to events like misreporting the death of Congresswoman Gabrielle Giffords. As an industry, Paul felt, we don’t have the right safeguards in pace yet.

What fascinated me about Paul’s talk, as ever, was the way that technology has been co-opted into the journalistic process. There are still people who are all too ready to dismiss Twitter as a place where celebrities discuss what they had for lunch, yet it has become a valuable tool. As web services ebb and flow, the current usage levels of Twitter may eventually go the way of MySpace and LiveJournal, but the principle of using mass peer-to-peer public short messaging as a way of tracking public sentiment and digging up information seems to have been comprehensively established.

Next...

As I said in my previous post about this panel session, my brain was left positively fizzing after attending both the Media Standards Trust/BBC College of Journalism “Data and news sourcing” and Paul Bradshaw’s inaugural lecture at City University in the same day. I’m sure there will be more blog posts to follow...

“currybetdotnet: Best of the blog 2011” brings together over 50 of the best posts on this blog from 2011, covering topics such as live blogging, community and social media for news websites, and the future of digital media. It features write-ups of talks by Guardian journalists including Paul Lewis, Matthew Wells, Andrew Sparrow and Chris Elliot, and behind the scenes looks at Guardian products like the Facebook and iPad apps. It also has transcripts of Martin Belam's talks at EuroIA, the UPA conference, Polish IA Summit, Content Strategy Forum 2011, FutureEverything and Hacks/Hackers London.

“currybetdotnet: Best of the blog 2011” for Kindle is £1.92.

this is a load of pony. if the internet hadn't existed, Paul would doubtless have found out who attended the demo by calling the NGOs and other organisations (university associations etc) who attended and contacting them over the phone. twitter just enabled him to do it faster and more efficiently. But it was Paul's persistence, and the cooperation of witnesses, which ensured the truth came out. In other words, it was good journalism for which Paul should be congratulated, which had almost nothing to do with Twitter at all. It's a tool, but so is a phone.

Well, it is mostly just a transcript of the things that Paul Lewis himself said, rather than my opinion. I think on the day he was very clear about the importance of his traditional journalism skills working alongside the new technology.

while sourcing details through media such as e.g. twitter can be useful in these times, it is extrememly open to poor information and misinformation and can be time consuming sifting through this as a result. One wonders whether in many cases traditional investigative methods will still be used?