The future sound of music according to the Guardian's Changing Media Summit

“In many ways, as a music fan, there probably hasn't been a better time to be a music fan” - Feargal Sharkey

One of the sessions that I attended at the recent Media Guardian Changing Media Summit was dedicated to the future of the music industry - a subject that has always been close to my heart, and which now has some interesting learning points for other forms of entertainment and digital media.

Feargal made his point that things had never been better for music fans because he believed that we underestimate the level of talent being produced in the UK, and because digital technology has made it easier than ever to consume whatever type of music you want, whenever and however you want - and now legally. He said the UK now had over 70 licensed digital music services, and that the key for the industry had been turning the 80 or 90 per cent of people who felt uncomfortable being pirates back into paying customers by providing the right services.

Paul Smernicki from Universal Music said that “Our digital music industry will continue to be as strong as our artist community”. He was delighted to see the number of digital services increasing, and reckoned you probably had to have niche taste and consumption habits not to have a digital service for you. The challenge for the industry was to connect people with the right service. He felt extremely positive, and said he was looking at “partners appearing on our balance sheet that simply weren’t there a year ago”.

He said it had definitely been tough and there had been lot of bad news stories in the industry, particularly in the sphere of physical retail. He then rather cheekily suggested that “the press seem to love to pick up on those negative things”, whereas I’d suggest that it was the industry itself that was providing those press releases and campaigns saying that piracy was killing music.

David Haynes from Soundcloud naturally saw technology as a great enabler for music:

“We are all sitting here with devices that can tap into nearly every single song that has ever been recorded, we can playlist them, and share them. There is a lot still to be worked out, but I think it is also the best ever time to be an artist.”

He suggested that it has never before been possible as an unknown artist in Brazil to collaborate directly with an unknown artist in Japan, as Soundcloud facilitates.

He also made the point, something which continues to astonish me, of the power and low cost of apps emulating synths and equipment that would previously have cost aspiring artists thousands of pounds to get hold of. When I think of the amount of kit I had to save up for and then physically carry around to do gigs in the mid-90s, compared to the music making power I carry around every day with my laptop or iPad, it boggles my mind.

David Haynes forsees a flood of new creativity, saying that he never used to take photos but now takes two or three a day. “This isn’t”, he said, “because I am seeing more interesting things”. Instead, it was simply down to Instagram allowing him to share those photos directly with his audience. A case of an app driving creation.

Also on the panel was Clive Dickens of Absolute, and he raised a couple of interesting things. He suggested that radio invented the word “playlist”, and so the widespread use of it on digital products just emphasises for them how much consumption habits have changed. As a brand they’ve realised they can no longer aim to be “all music, all of the time” but have instead started diversifying into speech and sports radio. He was excited about digital possibilities though, whilst still recognising the value of a “curator” in the way that John Peel introduced people to new music. He saw their business shifting slightly, enabled by digital consumption of their programming over IP, to remain one-to-many as a broadcaster, but transforming their digital advertising model to be more one-to-one and targeted.

A slight concern I had during the session, though, was that it still feels as if the likeliest threat to net neutrality in the UK is an unholy alliance of entertainment companies trying to protect analogue level revenues, ISPs who are struggling to grow market share, and a government that likes big businesses but doesn’t grasp technology.

Paul Bradshaw recently made a passionate plea for the news industry to be more vocal in protecting “the public realm” and to support net neutrality as a vital principle of using the web as a journalistic tool. It would be a great shame if the bundling of music, TV and film services with ISP provision began to unpick that fundamental property of the network.

Another thing that caught my ear was Feargal discussing “the myth of the long tail”. He said studies had shown that of the 13 million tracks made legally available by the industry, some 10 million of them had never even been downloaded once. It was still, he said, “a hits business”, for exactly the same reason that a book shop at an airport shifts copies of Dan Brown, and not, much to his own regret, volumes of poetry by Seamus Heaney.

The interesting thing for me in the end was seeing the panel so universally optimistic about the future of the business and the future of music consumption. Which came as a little bit of a surprise.

After years of being miserable about everything, it seemed like the music industry could finally see a way out of the gloom - and not just through the draconian powers they lobbied for from the last government, but by providing services that people wanted at a price they were prepared to pay. Indeed, Feargal even made the explicit point that he sees the rest of the entertainment industry with the same fearful haunted look in their eyes at the moment that the music industry had five or six years ago.

The panel all seemed to agree that the music industry had been the first to grapple with the kinds of problems now affecting the majority of sectors in the publishing and entertainment. Feargal said that they had emerged from it not because they had a giant crystal ball, but because as an industry they shifted and changed and experimented “without losing our shirts” until they had arrived at a model that was beginning to work. It looks likely that book publishers, film studios, and news organisations have got a few years yet of that to come, though it was reassuring to see that you can come out the other side. The music industry is facing diminished revenue - one figure quoted was that it has lost 31% of value since 2004 - but it looks like it might have stabilised revenue at a sustainable level.

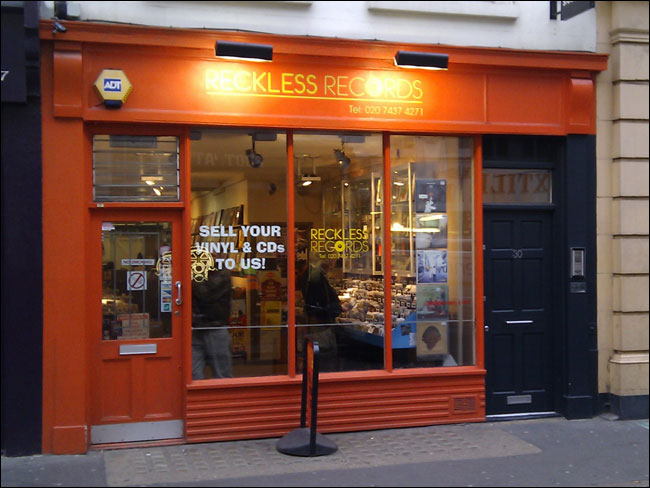

Finally, on a personal note, I’ve also spotted another pleasing little revival in the music industry. After going out of business, and a few years spent trading under a different name, Reckless Records, where I used to work, is back in its rightful place on Berwick Street in Soho. And every time I walk by it on my way to a London IA night at the Sense Loft, it makes me smile.