The 'digital election' and the diminishing role of the 'gatekeeper'

Tomorrow night I'm going to the launch of Nic Newman's Reuters Institute paper on "#UKelection2010, mainstream media and the role of the internet". I kept a keen eye on digital media during the election, including making my digital election timeline, and Nic interviewed me as part of his research. I'm looking forward to seeing the final paper.

The prominence of the TV debates stopped the 2010 campaign being seen as a truly 'Internet election', but what was clear to me was that usage of the Internet during the 2010 election demonstrated a further erosion of the traditional media role of 'gatekeeper'.

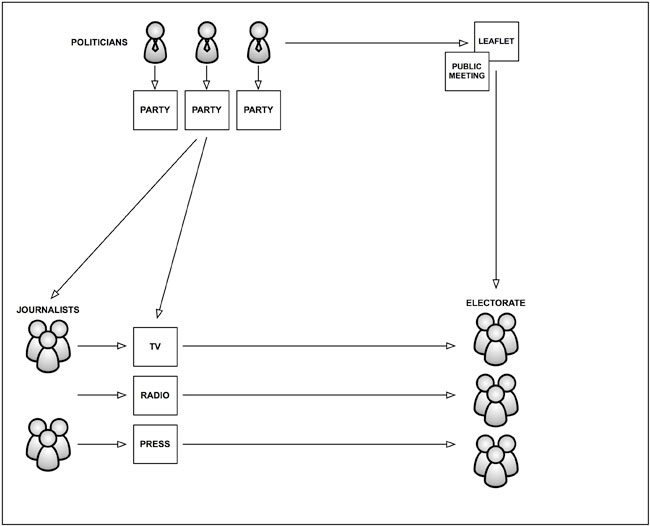

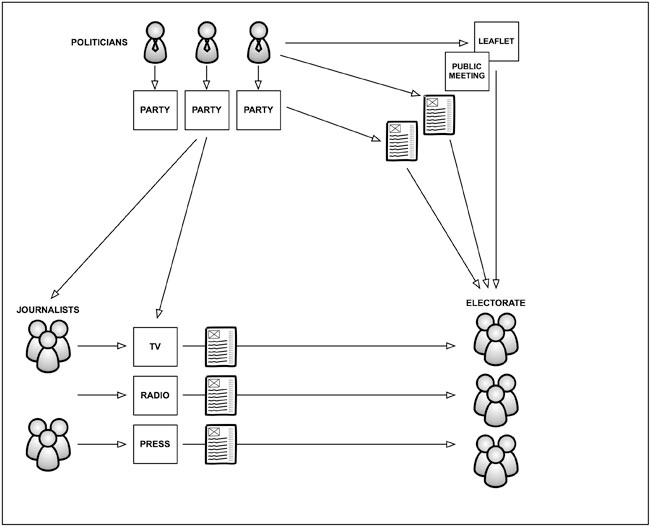

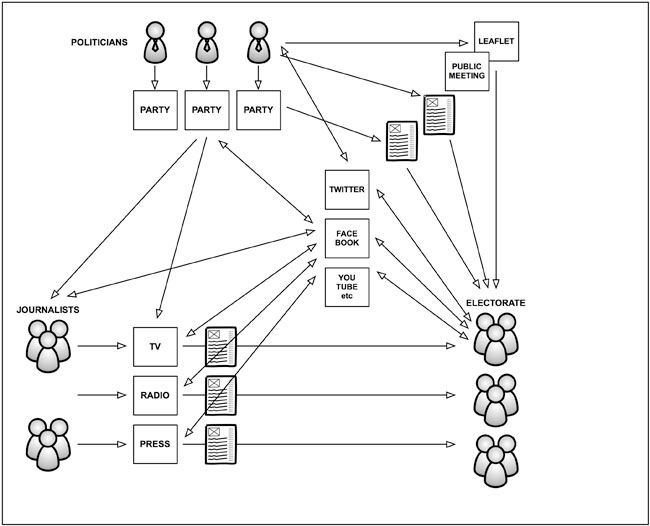

If we look back to the last pre-web election in 1992, the communication battle lines can be very neatly drawn. Individual politicians were corralled by party machinery, and individual journalists relied on traditional media companies granting them access to broadcast or distribute their reports. There was direct public communication from candidates to constituents only at public meetings and hustings, and in election leafleting with a limited geographical impact. This diagram broadly represents this scenario.

Digital communication began to impact electoral politics in the 1997 and 2001 elections. Traditional media outlets were increasingly operating cross-platform, as both newspapers and television stations began to have websites. Whilst BBC News Online was yet to be launched in 1997, a special election website from the BBC had a digital swing-o-meter amongst other attractions. Interaction between constituent and candidate via digital media was still rare, and whilst most parties had websites by 1996, there was not truly a notion of a 'digital campaign'.

The use of digital communications during a British election campaign was more 'mature' in 2005.

There was also increased digital publishing from the electorate, with blogging platforms having established themselves over the Geocities and 'Personal Home Pages' of the early web years. Third party tools also had an impact for the first time, with sites like TheyWorkForYou having been established during the lifetime of that Parliament. Despite the websites, communication was still mostly top-down however, mediated by party spin-doctors, newspaper editors and TV producers.

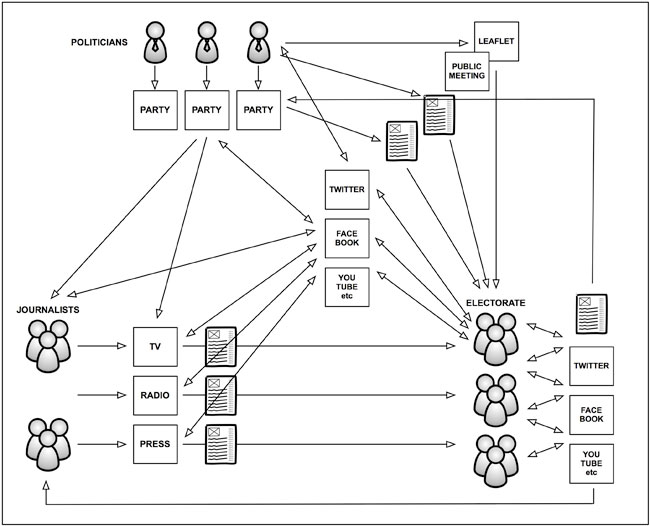

The addition of a social media ecosphere in the 2010 election has been transformative. Individual politicians and journalists had the tools to circumvent the party machinery gatekeepers and legacy monopoly publishing channels. Whilst The Guardian was writing a leader urging readers to vote Liberal Democrat (with caveats), followers of Guardian journalist Jemima Kiss on Twitter could see her avatar sporting support for the Greens.

Candidates were using social media to have contact with the electorate which was no longer bounded to a private conversation or a public meeting reported by a third party, but which was public, archivable and searchable. In some cases, like Stella Creasy, they used Twitter to keep a focus on local issues at times when the TV debates or 'bigotgate' were dominating the campaign. Others, like Stuart MacLennan, used Twitter to get deselected. This form of communication with the electorate featured a lot less direct management from the party machine than websites, leaflets or email marketing campaigns.

The most significant development for me, though, was not direct communication from individual politicians or media people to the public, but digital communication about the election amongst the public themselves. Of course, individuals have been able to publish their own content on a webpage since the early 1990s, but for the first time social media hubs like Twitter and Facebook allowed conversation between networks of people to unfold in real-time and in public.

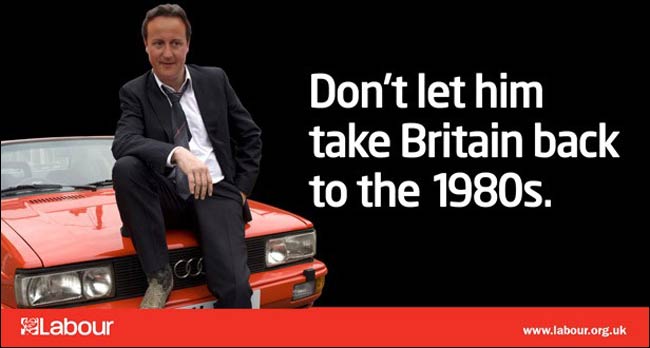

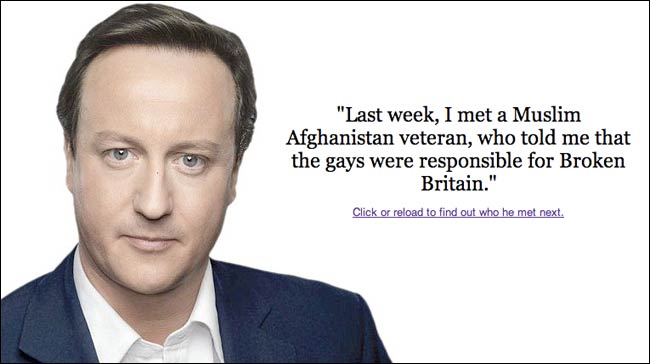

Would, for example, newspapers with a vested interest in maintaining the two party status quo have reported Nick Clegg's performance in the first TV debate so favourably if public opinion hadn't been so abundantly clear immediately as the debate unfolded? The network effect also meant that spoof posters and videos around the campaign were picked up and spread around online before making their way into amusing newspaper compilations.

I don't think anyone is in a position to make a call as to whether the 'digital election' changed the outcome of the vote. In fact, when I chatted with Nic about what I thought about new media during the campaign, my chief observation wasn't a political or digital one.

It was that British people love to be funny.

Much of the social media back channel around the election campaign seemed to be the equivalent of the truculent school kid at the back of the class putting their hand up to make a quip at the teacher's expense, seeking to gain recognition and approval from the rest of the class. The Facebook 'Like' button and Twitter's retweeting mechanism both reinforce this kind of behaviour, allowing users to instantly measure how popular or viral their own contribution to the campaign has been.

The 'digital election campaign' may not have changed the result, but it did make it more fun getting there.