'The curation gap' - what journalism can learn from "Citizen History"

My post yesterday, inspired by some of the fallout from the news:rewired event, generated some healthy debate on the blog and on Twitter. Scott Dougal suggested I was being a little unfair holding that article from that paper up as an example of professionalism journalism, and David Higgerson on Twitter said he just wished the debate 'would move beyond pointing out faults'. I promised him that I'd post how I thought everybody could live together happily ever after instead.

In the comments yesterday Ian Betteridge made a comparison with amateur astronomy and professional astronomers, and Kate Day posted a similar view on The Telegraph, using cooking as the analogy. For me, the analogy is history and historians, my academic background.

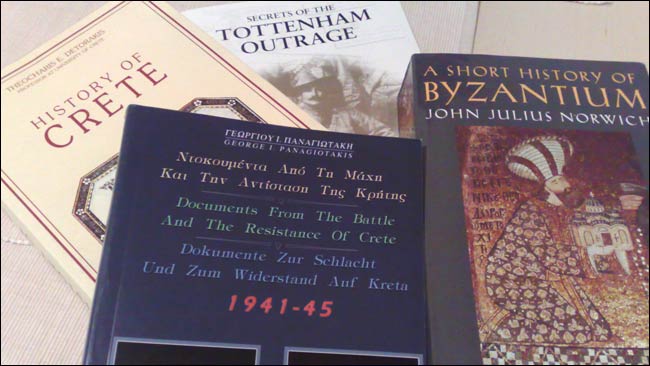

I've jokingly referred to some of the blog posts on here as "citizen history", but my bookshelves have a mix of historical output by professional and amateur alike. If I'm reading about Crete, then I have the authoritative tome of John Julius Norwich and his 'Short History of Byzantium', a single volume distillation of a career of scholarly effort. I also have the 'History of Crete' by Theocharis E. Detorakis. This is another scholarly work, but a local one, published in Iraklion by a Professor at the University of Crete. He isn't a world authority on history, but his local knowledge makes him ideal to put together such a study.

Specifically looking at the Second World War era on the island, I have a volume entitled "Documents from the battle and the resistance of Crete". Put together by George Panagiotakis, this is a compilation of primary source material. Closer to my current home I have a pamphlet by Patricia Collier called 'Secrets of the Tottenham Outrage'. It is self-published, and a classic example of single-topic amateur history.

Detorakis might not have the broad overview of the Byzantine Empire that John Julius Norwich had, but his take on Crete from a Greek perspective is definitive. Likewise, facing a specialist subject of 'The Tottenham Outrage' on Mastermind, I'd back Patricia Collier to take on any professional historian and win.

Within the sphere of the study of history, these all happily co-exist. So why do some people find it so hard to accept that the enthusiastic amateur, or the person on the ground who knows their local area, can contribute something valuable that can be broadly described as 'journalism'?

Well, in part, the fact that the 'business model' of history isn't perceived to be under quite as much stress as newspapers will have something to do with it. Historical societies up and down the land have been publishing pamphlets and small books for decades now, so they aren't quite the same new kid on the block as the threatening sounding 'digital citizen journalist'.

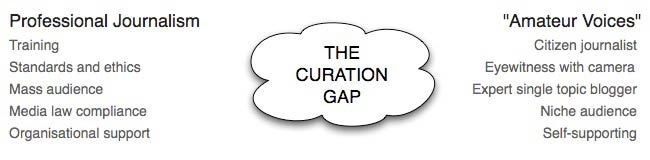

It seems to me that one of the missing pieces here is what I've come to describe as 'the curation gap'.

On the one hand, you have the professional journalist with their ethics, legal training, mass cross-platform audience, and a sense of serving as part of an organised 'fourth estate'. On the other, you have the 'amateur', the 'blogger', the 'citizen journalist', the 'eyewitness with mobile phone camera'. They might be a variety of things: self-commissioning, passionate, single-issue fanatics, in the right place at the right time, or determined not to describe themselves with the 'j' word at all. They will usually, either by virtue of the topic or the geographical area they cover, have a niche audience.

For me 'the curation gap' is that, at present, most mainstream media organisations seem lacking in the tools, or the will, or both, to bring the best of the voices in those niches and make them relevant to the mass audience. I believe that many of the traditional strengths of journalists make them ideally placed to carry out this role - the ability to build a network, the ability to prioritise and synthesize information, the ability to judge the authority of a source.

We'll get there when 21st century journalism follows the history model. When it sees the Patricia Collier as the respected niche expert, the George Panagiotakis as a collector of primary material, the Theocharis Detorakis as the domain expert - and doesn't just treat them as sources to be used or amateurs to be scorned, but as individual voices to curate and amplify.

Once again, Martin, you are spot on about what is so needed in journalism - I would add that in addition to journalists, there are information professionals and news librarians that are experts in deriving meaning and evaluating quality of information and sources - on and offline.

BTW I've read Norwich's Byzantium - excellent!

Perhaps the answer to the gap is that professionals be a bit more human, and the bloggers be more professional.

It's not that the mainstream media is "lacking in the tools, or the will" - it's that they don't want to put down the tiny bit of cold hard cash that niche content producers require.

A very nice perspective and article. I still like to refer to the "better" Citizen journalists as "columnists" rather than mainstream journalists.

Some columnists capture the news media in their niche better than a lot of journalists these days who are under pressure financially, contractually and ethically.

A friend of mine and his fellow 'citizen historian' produce this: ">The History Network

Well over 1,000,000 downloads.

(But then the offer is very slick and difficult to tell from the 'professional historian' - are there citizen journalism productions that look as polished).

I agree though that the difference is largely in the professional's willingness/reluctance to accept the amatuer as near-equal.