The tyranny of chronology: Part 3 - News atoms for the 21st century

This is the third in a series of posts based on the presentation given by Martin Belam at the 'News Innovation' unconference in London on July 10th 2009. You can find part one here.

News atoms for the 21st century

Yesterday, I was discussing how the 'atom' of news has moved from being the newspaper to the individual story. I think we need to go further, and disaggregate the neutrons and protons from that atom - the paragraphs and sentences that make up our stories.

I look at it this way.

Any decent news organisation that covers American politics will have some articles about US foreign policy.

And some of them will be about Cuba.

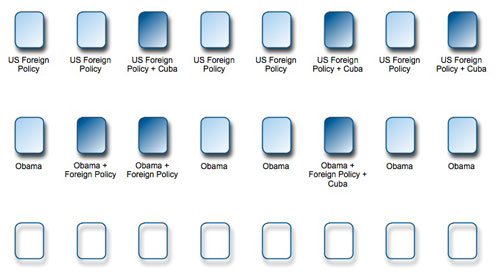

Any decent news organisation that covers American politics will have some article about Barack Obama's attitude to US foreign policy before he was elected. And it will have some articles about Barack Obama's attitude to foreign policy after he was elected President. And some of those articles will mention Cuba.

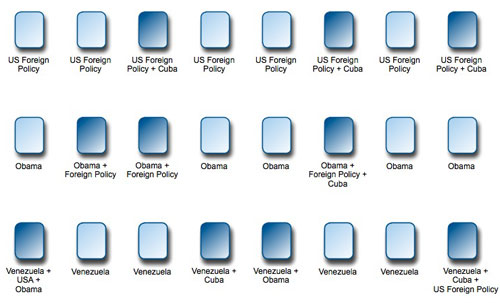

And a decent news organisation that looks at international relations in the region will have some articles about Venezuela, some of which will mention the USA, some of which will mention Cuba, and some of which might mention President Barack Obama and Cuba.

Now, at some point that decent news organisation is going to have someone type in the long-tail search query "obama foreign policy cuba venezuela"

There is useful information to uniquely answer that query scattered across the entire class of articles I've just described. Right now, the best we can do is get a computer to perform some maths on words, and stick them in a list. We then present that to the user ordered in a reasonably arbitrary way that the computer has calculated as 'relevance'. Or we just list them in, you've guessed it by now, reverse chronological order.

Wouldn't it be superb instead if, when faced with a long-tail query like "obama foreign policy cuba venezuela", we could answer not with a list, but with a relevant composite article that pulled together the key points from all those articles into one overview document - dynamically.

Well how are we going to achieve that?

Magic has to be programmed

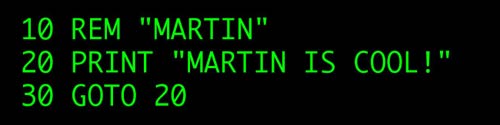

I'm of the generation that wrote my first computer program on a BBC Micro when I was at junior school. I expect it went something like:

10 REM "MARTIN"

20 PRINT "MARTIN IS COOL!"

30 GOTO 20

(In fact, I enjoyed writing that first program so much that I can achieve much the same thing - and little else - in a handful of programming languages now)

At that time I learnt, as we all know, that computers can do repetitive tasks very well. But there is a key thing we tend to forget, which is the second half of that equation.

Computers can perform repetitive tasks very quickly - once humans tell them what the task consists of.

So that's the challenge. How can we inform the machine of the contents of our chronological news in such a way that the machine can pull together the right overviews for our audience? People who have known me for a long while will not be surprised to find that my answer to this problem is the dreaded dull 'm' word - metadata.

Next...

Tomorrow, in part four of this series, I'll be looking at what the news industry can learn about metadata from librarians and Latin noun declensions.

While I see some good reasons to be able to extract data from several articles into one piece, I think that you lose context of what is being said. The danger of quoting any single person or any single document is that things get misinterpreted and the average person will just assume what is being said as fact and not even bother to go on and read more.

So yes, for some things I agree with you but for others I prefer to get full references to work from.

This is what's known as faceted classification! An ideal faceted system enables all the concepts and their relationships to be expressed. This can be done with complex classification schemes like UDC - the challenge is how to make that usable by translating it into natural language. The BBC LONCLASS system used for classifying programmes is an early example of the right approach (but very clunky technology).