The tyranny of chronology: Part 2 - On the subject of topics

This is the second in a series of posts based on the presentation given by Martin Belam at the 'News Innovation' unconference in London on July 10th 2009. You can find part one here.

On the subject of topics

Yesterday I was arguing that a recognisable pattern for news reporting was established by Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, which carefully recorded on an annual basis who did what to whom, where it happened and what the consequence was. We might be able to deliver the news digitally minute-by-minute nowadays, rather than annually, but the format remains broadly similar.

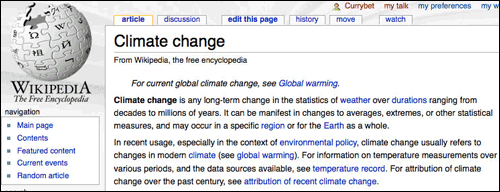

One of the consequences of this focus on chronology is that when our children want to do research on topics that news organisations have produced acres of coverage of, they find themselves turning to Google and Wikipedia, not The Times and the BBC.

This is not to be all 18th century and imperialistic about it, but how, with so much content creation talent at our disposal, in the lingua franca of the world, did we end up here?

I'd argue that it is in part because of our obsession with chronology.

British news sources have made moves to combat this. The Daily Mail, Telegraph, Guardian and BBC all have some sort of keyword or topic based aggregation pages in their current offering.

But if you look closely, what we are mostly still doing is displaying stories on a particular topic in reverse chronological order.

Of course there are links to background explainers, Q & As, database and comment and analysis. But where does this opening paragraph come from?

"The United Kingdom Parliamentary expenses scandal was a major political scandal triggered by the publication of expense claims made by members of the United Kingdom Parliament over several years. Public outrage was caused by disclosure of widespread actual and alleged misuse of the permitted allowances and expenses claimed by Members of Parliament (MPs), following failed attempts by parliament to prevent disclosure under Freedom of Information legislation."

Wikipedia.

It is the unpaid legions there that have managed to distill the essence of the story into two sentences. It is the first bit of content you hit when you reach their highly search engine optimised and trusted domain page about the phrase 'MPs Expenses'.

Look at our collective topic pages today, and instead of the kernel of the story, you'll mostly see a drip-drip of recent stories featuring figures at the periphery of the sorry tale.

When news becomes history

But I know we can do better - because we demonstrate it all the time with 'old' news. When we hit anniversaries that we can plan for, like the moon landing, our news media in the UK put fantastic packages of material together that provide context, background information, and which will be long-lasting resources on the Internet. They might have new content, interviews and features, but they don't say 'Moon landing - latest'.

But we don't seem to put these packages together until long after a story has ceased being 'news' and has started to become 'history'.

The thing is, we have accepted that our 'atom' has changed. We used to package up exactly the right amount of news to fit into a printed product, and sell it as a bundle. TV and radio production still revolves around getting news of the right length to fit the transmission slot.

But digital media is disaggregated.

Users are just as likely to want to hear one item from the 6 O'Clock news, played back via the BBC News website. Or they will simply reach one page of a story via Google. There is no longer any of that context that forms part of the language of news - the unspoken rules that tell you that if something is on page 13 it is less important than something on page 4.

For the last decade we've been carefully perfecting the art of breaking news down into the atom of 'the story'. And then essentially stacking them up in reverse chronological order. The user coming to a piece is expected to understand the back-story of any one piece, just as they would in print. However, digital formats no longer physically constrain us in this way.

How can we escape this obsession we have with reverse chronology and producing news of exactly 'the right size'?

Well, I think we need to start thinking smaller. The story might be our 'atom' of content, but the paragraphs and sentences are our neutrons and protons.

Next...

Tomorrow, in part 3 of this series, I'll be looking at how I see the potential for serving our audience in a way that goes beyond chronology and the simple search mechanisms we have available today.

Very interesting article Martin, the Internet is changing the way we get our informations and we find ourselves looking through "crap" news, in our search for information. People more and more tend to want small bits of information instead of comprehensive sources of information on a specific topic...