"You are what you measure" - why the music industry should adopt user-centred charts

In my line of business, we have a mantra - "you are what you measure". If you decide page views are your KPI, then you can increase those by simply splitting articles across three pages. If you decide time spent on the page is your main measure of success, then you can publish longer articles and puts lots of images in so it requires more scrolling, and so on.

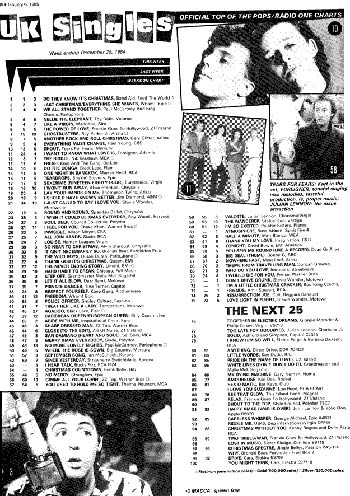

The music industry measures success by 'the charts', and the charts measure sales.

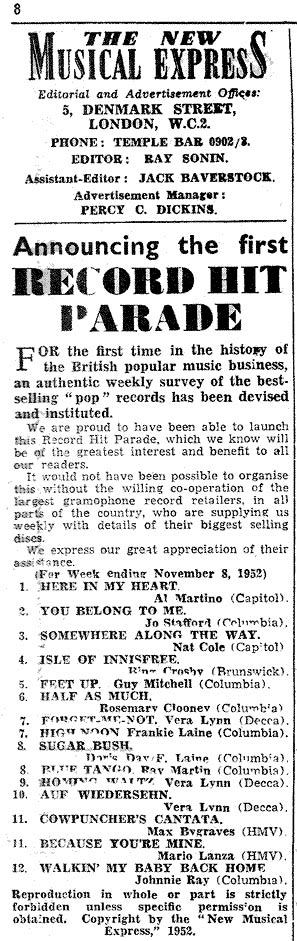

Charts are, and always have been, simply a marketing tool. It was back in the fifties that it was deemed that the number of sales of physical sound recording artifacts was the chief marketing tool the music industry needed. Prior to the first NME singles chart in the UK, popularity was determined by the sales of sheet music.

And of course, the industry measured what was easy to measure.

Sales figures used to be a fudge between what had been physically shipped from the warehouse to the shop, mixed with what had been written down in 'the chart diary'. Later, electronic readers, EAN codes, and shop assistants did the job of tracking stock.

The only other traditional measure of popularity has been radio play.

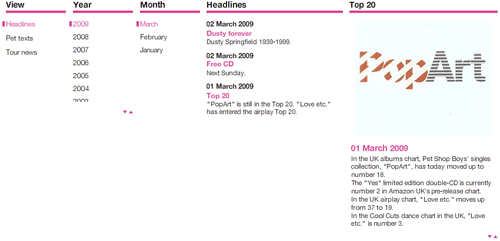

So this week the official Pet Shop Boys website was boasting that forthcoming single 'Love etc' had hit the top twenty playlist chart, and new album "Yes" was number 2 in Amazon's pre-release chart.

But what does a 'playlist' or 'pre-release' chart actually mean to the consumer in the digital era?

It means: "Great, the track is on radio playlists, but I still can't legitimately buy it."

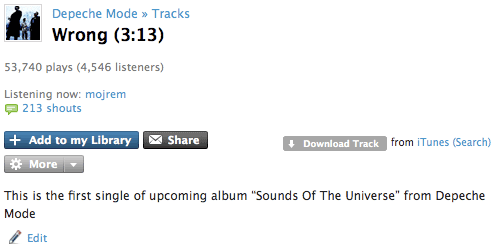

Put it this way, Depeche Mode's "Wrong" doesn't come out in the UK until April 6th. I've already been through 3 different 'leaked' versions of it on my iPod of varying quality. I'd be happy to buy it and pay for it right now, but although the manufacturing and distribution costs have fallen to almost zero, nobody will sell it to me in the UK until that arbitrary release date.

The reason for this is to bottle-up demand until everybody makes their purchase in the same week, in order to maximise the track's impact in the sales-based chart. It used to be that The Jam going straight into the singles chart at #1 was an event because it was so abnormal. Now, if you can't get your album's lead-off single into the top 3 in the first week, it is considered a flop.

There is a new set of data in town though. One that has been enabled by the Internet and the network effect.

Attention data.

If the music industry was to start using the attention data collected by last.fm or Spotify or the iTunes Genius feature, they could work on a marketing tool that prolonged the exposure of their major releases. Instead of frustrating customer demand until you can shift a load of units in a single 7 day period, the charts could reflect how popular tracks were after they were sold. They could also reap some marketing benefit from the pirate P2P versions of track that are being played, but not purchased.

As I say, you are what you measure.

If music industry charts moved away from the brute force approach of producing multiple formats and manipulating sales into an artificially short window, and more towards using attention data, they might actually end up rewarding the artists who made the music that people enjoyed the most.