The business of "Rip, Mix and Burn" at NESTA

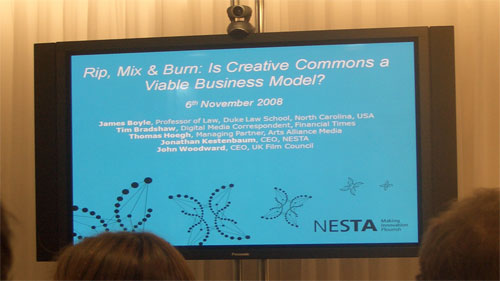

On Thursday I went to the HQ of innovation supporting NESTA for an evening event with the title "Rip, Mix & Burn: Is Creative Commons a Viable Business Model?". A panel of 4 were addressing the issue of where Creative Commons Licensed content fitted into the media ecosystem.

James Boyle

Opening the session was James Boyle - one of the legal eagles behind the framework of Creative Commons Licenses. He was at great pains to state that he was not an 'apostle' for CC, nor did he think it was applicable for everybody, but, as John Woodward later pointed out, for someone who was not 'evangelizing', he got "a lot of Psalms into his talk".

James began with a video illustrating the worth of Creative Commons content, made by Bob Dylan's son, soundtracked by Nine Inch Nails, and beautifully illustrated with lots and lots of Creative Commons licensed images. Boyle made the key point that leaving aside the arguments about commercial value of material, the Creative Commons framework allowed that video to be made without the laborious process of "rights clearance", which he thought even the mention of would give some people in the audience the shudders.

I couldn't help notice, though, that whoever was operating the computer cut the video playback short during the credits, thus removing some of the attributions which were, presumably, a staple part of the majority of the Licenses attached to the material used.

Boyle was keen to stress that the model wasn't right for everyone. An example that kept cropping up during the evening was J.K. Rowling. In trying to get the first Harry Potter book published she had to hawk the manuscript around publisher after publisher. Eventually one publisher took the plunge, and she is now one of the richest and most powerful authors on the planet. On the other hand, she might have given up pitching to traditional publishers, put the first novel out on the web under a CC License, and instead have all of 150 dedicated online fans.

That would be better than the position she was in, but effectively settling for limited distribution on the web using Creative Commons would have restricted her commercial potential. The premise that if you are doing nothing with content, giving it way for free can't 'be worse' is fine, unless giving it away has a huge opportunity cost.

Despite his claim to not be a cheerleader, Boyle was impassioned about the power of Creative Commons to transform culture and the educational potential of the license. He also had a neat range of one-liners:

"To publish my book Yale is paying me a substantial proportion of my daughter's college fees"

"Any set of rules that makes jazz illegal is per se wrong" [1]

"Don't experiment half-heartedly. Don't put the content behind seventeen notices saying don't do this, don't do bad things, and don't make fun of the Queen."

I particularly liked "Creative Commons is a tool, like a screwdriver. Screwdrivers are not an attack on hammers". I was amused by the fact that the tiny precise nuanced tool represented Creative Commons, whilst the old regime of copyright got to be represented by the brute force of the hammer.

John Woodward

John Woodward was next, and he put a bit of realism into the cries to free all of our archives under a CC License. He pointed out that the BFI only really owns around 1% of their archive, and don't have the power to re-assign rights. He also pointed out that having the content, and giving it away for free seems like a zero sum equation. However, he wanted to know who would pay for digitising the content and putting the context around it. He couldn't quite bring himself to use the dreaded 'metadata' word, but it was obvious that this was what he meant.

Where I disagreed a bit with John was over some of the movie industry approaches to pirate distribution. He said that the linear staggered distribution chain of theatrical release, rental DVD release, retail DVD release, pay-TV distribution and free-to-air distribution was "how it has always been". That clearly isn't true for the UK, where subscription TV was inserted into the chain in the 90s, and rental distribution on VHS and Beta was a novelty in the late 70s.

I'm not clear that digital distribution has currently been slotted into the correct place in the chain. John Woodward said that consumers are increasingly of the opinion that if you are heavily promoting 'Quantum of Solace' now, why can't I watch it at home when I want. It seems to me that studios could potentially retain a larger share of their revenue if they went direct to the consumer digitally. In fact, despite the changes in technology, the the cost of producing "movies" and indeed their format, is still based on the model of projecting some very expensively printed celluloid onto a white wall on the far side of a very large room.

Thomas Hoegh

The Ibsen-quoting Norwegian Thomas Hoegh was the third person to speak. He painted an amusing if bleak picture of what television was like for him growing up in Norway. There was only one state TV channel which on Tuesday evenings presented discussion programmes about books and religion - not really likely to get the young pulse racing. He contrasted that situation with the vast array of media production being made today, including that by the users themselves, saying that there are so many more places where he can "spend his eyeballs".

He suggested that one of the biggest issues for media companies was the fact that they had little ability now to predict where their businesses will be in the future. He gave the example of one of the major studios sitting down to plan their development schedule for the next ten years. How can they budget if they don't know the way that digital technology is going to impact on their business and revenue in the next two years, let alone in a decade.

Another issue for Hoegh was that nobody really agrees on the value of the 'content' anymore. People still pay £60 to go and see someone play live at the O2, since that has a one-off event value to it. However, they'll happily download that same artist's music and videos for free using BitTorrent, because they have grown accustomed to getting that type of content for free. Thomas suggested that everyone had their own idea of what content was worth, and all of them were wrong.

Tim Bradshaw

The fourth panelist was Tim Bradshaw, a digital media journalist for the FT. He himself may have had his Flickr photos used under a CC License for an European Commission study into viral diseases, but he repeatedly made the point that he didn't see how Creative Commons made business sense for the individual. He felt that the 'long tail' had persistently made money for the aggregator, but not for the content producer. He pressed James Boyle for figures on just how much money people had made from CC License content. He suggested that the most money to be made might be for the Creative Commons group themselves, acting as a content aggregator for people who don't have ambitions to be financially successful.

Question time

A couple of good points came out during the audience question session.

James Boyle illustrated a story with the example of a small publisher. They started making some of their older back catalogue available online for free under a CC License, and found that sales of the stuff they had given away improved, whilst those that remained languishing in obscurity stayed that way.

Thomas Hoegh expressed the view that if movie studios have to reduce their outgoings, there will still be blockbusters, it will just hopefully be things like the weak third Addams Family movie that get the chop. Most people in the room seemed quite pleased at that prospect.

The session finished with James Boyle getting a minute to sum up the topic, and he spoke with great enthusiasm about the education potential of Creative Commons licensed teaching materials that could be freely translated and re-combined and adapted to make resources for children all over the networked planet.

NESTA have made the session available online in both audio and video.

[1] I'm not sure that Vince Noir would agree. [Return to article]