Reckless Records RIP - Part 5: OK Computer

(or "Everything I know about second-hand record retail I learnt by being rude to customers at Reckless Records" by someone a bit like that bloke in 'High Fidelity')

This week I've been writing about my experiences working for Reckless Records during the 90s, and yesterday I was looking at the UNIX system the shop used to run, and how it got me back being interested in computers again.

I moved to start working in the Soho branch of secondhand retailer Reckless Records in 1996, and my ability to use computers was a significant factor.

This wasn't a case of applying for a promotion and going through a fair selection interview process like I would end up having to do at the BBC. It was simply decided that as the guy who really knew about computers at that branch, Gordon, was leaving, I'd have to go and replace him.

I was somewhat in awe of his reputation, because even if I knew my way around computers, I certainly was nowhere near having his specialist knowledge of U.S. Indie, Industrial and Reggae music.

At that time Reckless had two branches in London, linked by a leased ISDN line, with the UNIX server situated in the Soho shop. The system was a custom bit of retail software from the Wallace Haines company in the USA, where Reckless also had branches.

There were a couple of things about the computer system that were, on reflection, completely insane.

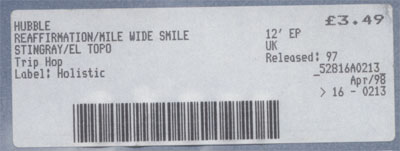

One of them was that when you processed a stock item, the system produced two stickers. One was customer-facing, with the item details, price, and a barcode.

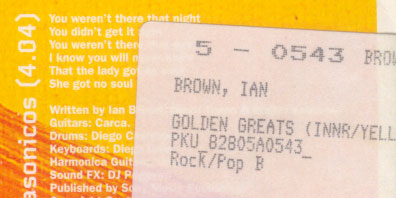

The second was to stick on the inner-sleeve or masterbag, used to file the actual vinyl or CD behind the counter.

The most important thing to keep track of stock was the PKU (Price-keeping unit number, I believe). A PKU at Reckless was made up of a code that included information on what store had processed the item, what format it was in, the year, the week number of the year, and the item number within that week.

The filing sticker meanwhile simply had abbreviated details of the artist and title, and the week and item number. And not the PKU.

Which meant that you couldn't get the unique PKU that identified the item from the sticker that was placed behind the counter. Or use the information on that sticker to look the item up on the system.

For all sorts of reasons this was a nightmare, especially as empty sleeves were stolen regularly from the racks. Without the PKU, which only appeared on the price-sticker, you couldn't even sell an item at a discount without the sleeve, because you didn't have access to the unique identifier.

In the end I just had to learn how to make up all of the codes in my head. This meant that if you gave me a CD Single or an LP or cassette, and said it was processed in Upper Street in 1995, I could deduce from that what the original PKU would have been.

I began to feel like one of those strange people who claim to be able to recognise any piece of classical music on vinyl just by looking at the grooves of the disc.

Eventually we got the system changed so that the file stickers did also have the PKU listed on it.

Another really mad thing was the annual 'inventory' check.

Once a year, for both accounting and shop management purposes, we needed to reconcile what we physically had in the branch to what the computer system thought we had in the branch.

This meant literally striping the barcode of every item in stock in the branch through the cash register terminals. That was done on a Saturday night after the shop shut, and whole swathes of staff would come in to tackle it for a couple of hours. We always laid on some free pizza and a bit of, though not too much, beer.

Most people drifted away for a night out clubbing at 10pm, and usually a couple of die-hards, including myself, would be at the branch until 3 or 4am striping in the codes.

Then you would print the first 'exceptions' report. This listed everything that the computer thought was in stock but which you hadn't entered the barcode for. And it also listed all the things that you striped the barcode for, but which the computer didn't think was in stock in that branch, which could happen for all sorts of reasons.

And so, on Sunday and Monday, the task for all staff was to hunt down these exceptions, and confirm whether we really did have these miracle items that shouldn't be there, and to try and locate the things that were missing.

As a branch manager it was a very stressful time of year, because the inventory check revealed how much stuff had been stolen by customers and staff, and how tight your control of your stock was.

The real lunacy, though, was that the software we used could not process another sale until the physical and the virtual inventories were reconciled.

Which meant that the shop had to close for two to three days each year whilst we were running around hunting to find all the missing and lost records and CDs. It meant that in order to recover a couple of hundreds of pounds worth of misplaced stock, and identify missing stock, you lost three days trading in each of the stores. It was sheer economic madness for a small business, dictated by the functionality of the computer system.

Next week I'll be continuing this secondhand record store nostalgia, and looking at how I first got interested in using the internet at Reckless.