Reckless Records RIP - Part 1: An End Has A Start

(or "Everything I know about second-hand record retail I learnt by being rude to customers at Reckless Records" by someone a bit like that bloke in 'High Fidelity')

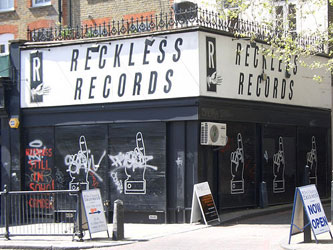

I found out, only via a brief mention in an article in the Guardian - "The Vinyl Frontier" by Adam Webb - that my old record shop Reckless Records had gone out of business in London.

A quick check of the Reckless website, which back in the late nineties I used to look after, but which I hadn't visited for a long time now, confirmed it to be true.

"Sadly we have to announce that Reckless Records has had to close down and has gone into liquidation after 24 years. The business of dealing in secondhand records and compact discs has become more and more difficult due to lots of factors, particularly the growth of internet trading, both at new and secondhand levels, and the impossibility of trying to keep abreast of falling prices in High Street stores and online retailers."

It is a real shame, but from having visited Reckless a couple of times on my last few trips to the UK, it seemed like the writing had been on the wall for a while.

At one point Reckless had four shops in London. Unfortunately the Camden branch never really took off, and the company was forced out of Islington when the rent spiralled upwards as Upper Street got trendier and trendier.

Even when I was still there - up until December 2000 - the store was feeling the pinch of the near constant sales of back catalogue CDs in HMV and Virgin between £4.99 and £6.99. At the same time the original Napster format was beginning to take file-sharing into the consciousness of serious music fans, whilst eBay had provided a one-to-one market for secondhand CDs, rather than a one-to-Reckless-to-one relationship that the shop relied upon.

The store I managed had unsuccesfully tried to branch out into secondhand DVDs and Games alongside the record, tapes and CDs of yesteryear, but didn't have the muscle to hire the additional specialist staff we really needed to do well in those areas.

I first started working for Reckless full-time 13 years ago, in 1994, just as the World Cup was starting in the USA.

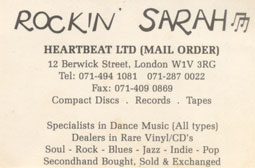

In my last week of studying at Leeds, I got a phone call from my mum. She had received the job offer on my behalf, from someone I previously used to work with in two different record shops, Note For Note in Walthamstow and then at Rockin' Sarah on Berwick Street in Soho.

She said she didn't really know what the job entailed, but that my soon-to-be-boss had said that the mail order department had its own neon sign, which was clearly an important detail to him.

It was brilliant news though, as it turned out that I didn't, after all, have to decide what to do with the whole of the rest of my life as soon as my final exams finished.

My initial job there was in the mail order department in the Upper Street branch in Islington. I still remember very clearly getting my first payslip, and walking down the street ecstatic to have received just over £700 for a month's work.

Measured by the standard of the student grant I have been receiving whilst at University the previous three years, that was an incredible three whole months money earned in just the one.

[I suspect a time-travelling version of myself from the future would have given the younger-me a heart seizure if future-me had passed on the information about how much you could earn as an information architect and internet consultant in 2007. Or, more likely, by mentioning the as-yet-unknown concept of student debt.]

In the mail order department my job was basically laying out monthly mail shots using PageMaker desktop publishing software, serving customers, and cleaning really rare records.

I must have spent at least four hours a day, nearly every day for two years, inhaling a weird top secret mixture of distilled water, alcohol and other chemicals used for the record cleaning machine.

Reckless had invested in a hand-built specialist Loricraft record cleaning machine.

The record to be cleaned was spun at around 78rpm, and you sprayed the cleaning mixture onto it. You then brushed it onto the surface, and made sure the mixture was evenly distributed along the width of the disc. Then you manoeuvred an arm, similar to that of a record player, onto the surface of the album. This was the nozzle of a small vacuum cleaner, housed in the cabinet of the machine, which then sucked up the accumulated dust and grit from the grooves.

Despite being genuinely Heath-Robinson in its crazy lash-up way, essentially a mini vacuum cleaner hidden in a teak-effect case, with cotton used to haul the suction nozzle across the grooves, it effectively rendered second-hand records looking 'as new' and added to their value.

Each month the mail order department used to send out a mini-catalogue mail shot of rare stock that had been accumulated in the previous four or five weeks.

Before the idea of simultaneously publishing the current stock of the shop on the internet arrived, the production of this catalogue was the main monthly focus of the mail order business.

We tracked customer interactions using a Microsoft Access database. We kept records on customer's names, addresses, spend, and the major artists whose records they had purchased - and all, at that time, without a concept of how the Data Protection Act might apply.

Customers were graded according to how many mail order transactions they had placed, and the total value of money they had spent with Reckless via mail order, on a scale of 1 to 5.

Grade 5 customers had spent the most, and were the first to be issued with the new catalogue each month, since they were the most regular repeat customers with the highest spend.

I used to carefully pack all of the mini-catalogues, and then post them in a staggered fashion, sending those to Japan and the U.S.A. first, then to Europe the next day, and then to the UK. The theory was that they would hopefully hit everybody's letter box at the same time, and give all of our best customers a chance to get the best items from the list each month.

Once the '5' customers had got their mail shots, we would then mail the 4 & 3 grade customers with the mail shot, and after that, depending on how much remained unsold, we would do further mail-outs.

Whilst it was an excellent system for ensuring that we drove revenue from all of our biggest customers on the first couple of days of the 'mail shot month', it certainly had its flaws.

Not least of which was that since trading in rare records is a 20th century form of trading in antiques, Reckless generally had only one copy of any item listed in the mail shot.

Since it went to the grade 5 customers first, it became a self-fulfilling prophecy that the grade 5 customers bought the rarest and most expensive items - since they got first bite at the cherry. Grade 2 and 3 customers would often try and order items that were already sold, and would not therefore be able to improve their customer grading. Which meant they still didn't get access to the better stock the following month.

With hindsight, I would have built a more sophisticated feedback loop into the system, that took into account what the value of someone's intended ordering would have been had all the items they'd ever wanted always been in stock, and placed more of a premium on attracting new customers.

In the next part of this series I'll be wandering further down memory lane into my days at Reckless, looking at the relationship with Record Collector magazine, and the perils of under-pricing rare records.