Engineering parallels at the Science Museum

I was in London's Science Museum yesterday, and couldn't help noticing that there some parallels and lessons to be learnt for our own times and developments in new media technologies.

Throughout the modern debate on computer software patents we have been assured by those in support of them that patents allow companies to innovate and help technological development. That view doesn't seem to be shared by the Science Museum's caption writer for their energy section. Talking about the rise of steam power one exhibit reads:

"In 1769, James Watt had taken out a patent that allowed him to dominate steam-engine design and improvement. As a result, other engineers were prevented by law from developing new, alternative designs."

When the patent expired other engineers were able to innovate again, particularly Richard Trevithick. He experimented with using steam under a much higher pressure, and as a result was able to build smaller and more powerful engines, which enabled him to build the first locomotive railway engine capable of hauling a load. Researching for this article it also seems that Watt himself was hindered by a patent that had been awarded to John Steed. Just think, without those patented monopolies on innovation, Britain may have developed the railway engine twenty or thirty years earlier, changing the development of early locomotive engines like Stephenson's "The Rocket" and "Puffing Billy" which are also on display in the Science Museum.

Of course, meddling with history and advancing the speed of the industrial revolution would no doubt bring a visit to the UK from the Doctor to sort it out, and I have to confess that most of my knowledge of Isambard Kingdom Brunel and the iconic image of him derives from having read the Doctor Who novel "Reckless Engineering"

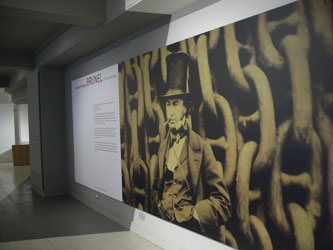

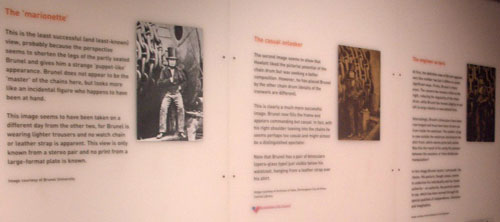

The Science Museum currently has a small temporary exhibition devoted to the history of that photo of Brunel, called "Brunel - Fame and Fate", pointing out that it was probably the first occasion a public figure tried to manipulate their image through the medium of photography. Brunel posed for three photographic portraits in front of those massive chains, and the one that is well known seems to have been chosen because it illustrates him at his most commanding.

The photograph was taking during the construction of his last major project - The Great Eastern or SS Leviathan as she was originally known - at the time an attempt to build what was at the time the world's largest metal boat.

Although in the end it was seen as a financial failure, the ship did succeed in laying the first trans-Atlantic telegraph cables, and is such a powerful image of a ship in maritime history that there is even a website specifically devoted to trading original parts and memorabilia from the ship.

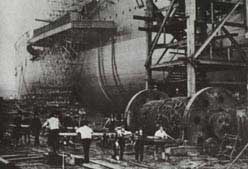

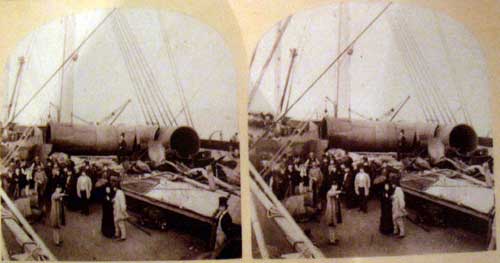

Thanks to the advance of photography at the time we actually have a pictorial record of the last stages of this mammoth undertaking. They reminded me of the pictures you can see in the walkways above Tower Bridge of the construction of that London landmark, another remarkable feat of Victorian engineering with metal.

It also made me realise that actually there hasn't been that much change over the last two centuries between the processes of mechanical engineering and the sort of software engineering I've been involved in. Three parallels in particular stood out for me.

1. Client requirements will cause difficult design constraints

The Great Eastern was required to be able to navigate the shallow Hooghly River in India, which meant that the propeller she was fitted with had to be too small to power the vessel alone. Brunel therefore also fitted 17 metre steam powered paddles to the sides of the ship. And it had sails. In fact the only means of known marine propulsion it didn't feature was a galley deck of slaves with oars.

2. A botched launch will attract more publicity than a successful one

Just ask the team behind the 1901 census website . Due to the extraordinary size of The Great Eastern it had to be launched into the Thames sideways in a new process. This didn't go without a hitch and the first attempt had to be abandoned when the ship got stuck, causing fatalities, and it took a further three months to get her into the water. The interest and publicity around the failed launch was enormous, to the extent that there is still a photographic record of the furore.

3. Once you launch a successful new technology, there is always someone there making money off the back of it

One of the displays in the temporary Brunel exhibition were sets of 'stereoscopic postcards' of pictures of The Great Eastern that were sold as a huge success by someone other than Brunel or the construction companies involved in building the ship itself.

what a boring webpage. I could do better